- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Globalhead Page 3

Globalhead Read online

Page 3

Vlad’s pale eyes bulged as they fell on my framed official photograph of Laika, the cosmonaut dog. The dog had a weird, frog-like, rubber oxygen mask on her face. Just before launch, she had been laced up within a heavy, stiff space-suit—a kind of canine straitjacket, actually. Vlad frowned and shuddered. I guess it reminded him of his recent unpleasantness.

Vlad yanked my vodka bottle off the kitchen counter, and headed outside without another word. I watched him through the window—he looked well enough, sipping vodka, picking blackberries, and finally falling asleep in the hammock. His suitcase contained very little of interest, and his boxes were mostly filled with books. Most were technical, but many were scientific romances: the socialist H.G. Wells, Capek, Yefremov, Kazantsev, and the like.

When Vlad awoke he was in much better spirits. I showed him around the property. The garden stretched back thirty meters, where there was a snug outhouse. We strolled together out into the muddy streets. At Vlad’s urging, I got the guards to open the gate for us, and we walked out into the peaceful birch and pine woods around the Klyazma Reservoir. It had rained heavily during the preceding week, and mushrooms were everywhere. We amused ourselves by gathering the edible ones—every Russian knows mushrooms.

Vlad knew an “instant pickling” technique based on lightly boiling the mushrooms in brine, then packing them in ice and vinegar. It worked well back in our kitchen, and I congratulated him. He was as pleased as a child.

In the days that followed, I realized that Vlad was not anti-Party. He was simply very unworldly. He was one of those gifted unfortunates who can’t manage life without a protector.

Still, his opinion carried a lot of weight around the Center, and he worked on important problems. I escorted him everywhere—except the labs I wasn’t cleared for—reminding him not to blurt out anything stupid.

Of course my own work suffered. I told my co-workers that Vlad was a sick relative of mine, which explained my common absence from the job. Rather than being disappointed by my absence, though, the other engineers praised my dedication to Vlad and encouraged me to spend plenty of time with him.

I liked Vlad, but soon grew tired of the constant shepherding. He did most of his work in our dacha, which kept me cooped up there when I could have been out cutting deals with Nokidze or reporting on the beatnik scene.

It was too bad that Captain Nina Bogulyubova had fallen down on her job. She should have been watching over Vlad from the first. Now I had to tidy up after her bungling, so I felt she owed me some free time. I hinted tactfully at this when she arrived with a sealed briefcase containing some of Vlad’s work. My reward was another furious tongue lashing.

“You parasite, how dare you suggest that I failed Vladimir Eduardovich? I have always been aware of his value as a theorist, and as a man! He’s worth any ten of you stukach vermin! The Chief Designer himself has asked after Vladimir’s health. The Chief Designer spent years in a labor camp under Stalin. He knows it’s no disgrace to be shut away by some lickspittle sneak …” There was more, and worse. I began to feel that Captain Bogulyubova, in her violent Tartar way, had personal feelings for Vlad.

Also I had not known that our Chief Designer had been in camp. This was not good news, because people who have spent time in detention sometimes become embittered and lose proper perspective. Many people were being released from labor camps now that Nikita Khrushchev had become the Leader of Progressive Mankind. Also, amazing and almost insolent things were being published in the Literary Gazette.

Like most Ukrainians, I liked Khrushchev, but he had a funny peasant accent and everyone made fun of the way he talked on the radio. We never had such problems in Stalin’s day.

We Soviets had achieved a magnificent triumph in space, but I feared we were becoming lax. It saddened me to see how many space engineers, technicians, and designers avoided Party discipline. They claimed that their eighty-hour work weeks excused them from indoctrination meetings. Many read foreign technical documents without proper clearance. Proper censorship was evaded. Technicians from different departments sometimes gathered to discuss their work, privately, simply between themselves, without an actual need-to-know.

Vlad’s behavior was especially scandalous. He left top-secret documents scattered about the dacha, where one’s eye could not help but fall on them. He often drank to excess. He invited engineers from other departments to come visit us, and some of them, not knowing his dangerous past, accepted. It embarrassed me, because when they saw Vlad and me together they soon guessed the truth.

Still, I did my best to cover Vlad’s tracks and minimize his indiscretions. In this I failed miserably.

One evening, to my astonishment, I found him mulling over working papers for the RD-108 Supercluster engine. He had built a cardboard model of the rocket out of roller tubes from my private stock of toilet paper. “Where did you get those?” I demanded.

“Found ’em in a box in the outhouse.”

“No, the documents!” I shouted. “That’s not your department! Those are state secrets!”

Vlad shrugged. “It’s all wrong,” he said thickly. He had been drinking again.

“What?”

“Our original rocket, the 107, had four nozzles. But this 108 Supercluster has twenty! Look, the extra engines are just bundled up like bananas and attached to the main rocket. They’re held on with hoops! The Americans will laugh when they see this.”

“But they won’t.” I snatched the blueprints out of his hands. “Who gave you these?”

“Korolyov did,” Vlad muttered. “Sergei Pavlovich.”

“The Chief Designer?” I said, stunned.

“Yeah, we were talking it over in the sauna this morning,” Vlad said. “Your old pal Nokidze came by while you were at work this morning, and he and I had a few. So I walked down to the bathhouse to sweat it off. Turned out the Chief was in the sauna, too—he’d been up all night working. He and I did some time together, years ago. We used to look up at the stars, talk rockets together … So anyway, he turns to me and says, ‘You know how much thrust Von Braun is getting from a single engine?’ And I said, ‘Oh, must be eighty, ninety tons, right?’ ‘Right,’ he said, ‘and we’re getting twenty-five. We’ll have to strap twenty together to launch one man. We need a miracle, Vladimir. I’m ready to try anything.’ So then I told him about this book I’ve been reading.”

I said, “You were drunk on working-hours? And the Chief Designer saw you in the sauna?”

“He sweats like anyone else,” Vlad said. “I told him about this new fiction writer. Aleksander Kazantsev. He’s a thinker, that boy.” Vlad tapped the side of his head meaningfully, then scratched his ribs inside his filthy houserobe and lit a cigarette. I felt like killing him. “Kazantsev says we’re not the first explorers in space. There’ve been others, beings from the void. It’s no surprise. The great space-prophet Tsiolkovsky said there are an infinite number of inhabited worlds. You know how much the Chief Designer admired Tsiolkovsky. And when you look at the evidence—I mean this Tunguska thing—it begins to add up nicely.”

“Tunguska,” I said, fighting back a growing sense of horror. “That’s in Siberia, isn’t it?”

“Sure. So anyway, I said, ‘Chief, why are you wasting our time on these firecrackers when we have a shot at true star flight? Send out a crew of trained investigators to the impact-site of this so-called Tunguska meteor! Run an information-theoretic analysis! If it really was an atomic-powered spacecraft like Kazantsev says, maybe there’s something left that could help us!”

I winced, imagining Vlad in the sauna, drunk, first bringing up disgusting prison memories, then babbling on about space fiction to the premier genius of Soviet rocketry. It was horrible. “What did the Chief say to you?”

“He said it sounded promising,” Vlad said airily. “Said he’d get things rolling right away. You got any more of those Kents?”

I slumped into my chair, dazed. “Look inside my boots,” I said numbly. “The Italian ones.”

“Oh,” Vlad said in a small voice. “I sort of found those last week.”

I roused myself. “The Chief let you see the Supercluster plans? And said you ought to go to Siberia?”

“Oh, not just you and me,” Vlad said, amused. “He needs a really thorough investigation! We’ll commandeer a whole train, get all the personnel and equipment we need!” Vlad grinned. “Excited, Nikita?”

My head spun. The man was a demon. I knew in my soul that he was goading me. Deliberately. Sadistically.

Suddenly I realized how sick I was of Vlad, of constantly watchdogging this visionary moron. Words tumbled out of me.

“I hate you, Zipkin! So this is your revenge at last, eh? Sending me to Siberia! You beatnik scum! You think you’re smart, blondie? You’re weak, you’re sick, that’s what! I wish the KGB had shot you, you stupid, selfish, crazy …” My eyes flooded with sudden tears.

Vlad patted my shoulder, surprised. “Now don’t get all worked up.”

“You’re nuts!” I sobbed. “You rocketship types are all crazy, every one of you! Storming the cosmos … well, you can storm my sacred ass! I’m not boarding any secret train to nowhere—”

“Now, now,” Vlad soothed. “My imagination, your thoroughness—we make a great team! Just think of them pinning awards on us.”

“If it’s such a great idea, then you do it! I’m not slogging through some stinking wilderness …”

“Be logical!” Vlad said, rolling his eyes in derision. “You know I’m not well trusted. Your Higher Circles don’t understand me the way you do. I need you along to smooth things, that’s all. Relax, Nikita! I promise, I’ll split the fame and glory with you, fair and square!”

Of course, I did my best to defuse, or at least avoid, this lunatic scheme. I protested to Higher Circles. My usual contact, a balding jazz fanatic named Colonel Popov, watched me blankly, with the empty stare of a professional interrogator. I hinted broadly that Vlad had been misbehaving with classified documents. Popov ignored this, absently tapping a pencil on his “special” phone in catchy 5/4 rhythm.

Hesitantly, I mentioned Vlad’s insane mission. Popov still gave no response. One of the phones, not the “special” one, rang loudly. Popov answered, said, “Yes,” three times, and left the room.

I waited a long hour, careful not to look at or touch anything on his desk. Finally Popov returned.

I began at once to babble. I knew his silent treatment was an old trick, but I couldn’t help it. Popov cut me off.

“Marx’s laws of historical development apply universally to all societies,” he said, sitting in his squeaking chair. “That, of course, includes possible star-dwelling societies.” He steepled his fingers. “It follows logically that progressive Interstellar Void-ites would look kindly on us progressive peoples.”

“But the Tunguska meteor fell in 1908!” I said.

“Interesting,” Popov mused. “Historical-determinist Cosmic-oids could have calculated through Marxist science that Russia would be the first to achieve communism. They might well have left us some message or legacy.”

“But Comrade Colonel …”

Popov rustled open a desk drawer. “Have you read this book?” It was Kazantsev’s space romance. “It’s all the rage at the space center these days. I got my copy from your friend Nina Bogulyubova.”

“Well …” I said.

“Then why do you presume to debate me without even reading the facts?” Popov folded his arms. “We find it significant that the Tunguska event took place on June 30, 1908. Today is June 15, 1958. If heroic measures are taken, you may reach the Tunguska valley on the very day of the fiftieth anniversary!”

That Tartar cow Bogulyubova had gotten to the Higher Circles first. Actually, it didn’t surprise me that our KGB would support Vlad’s scheme. They controlled our security, but our complex engineering and technical developments much exceeded their mental grasp. Space aliens, however, were a concept anyone could understand.

Any skepticism on their part was crushed by the Chief Designer’s personal support for the scheme. The Chief had been getting a lot of play in Khrushchev’s speeches lately, and was known as a miracle worker. If he said it was possible, that was good enough for Security.

I was helpless. An expedition was organized in frantic haste.

Naturally it was vital to have KGB along. Me, of course, since I was guarding Vlad. And Nina Bogulyubova, as she was Vlad’s superior. But then the KGB of other departments grew jealous of Metallurgy and Information Mechanics. They suspected that we were pulling a fast one. Suppose an artifact really were discovered? It would make all our other work obsolete overnight. Would it not be best that each department have a KGB observer present? Soon we found no end of applicants for the expedition.

We were lavishly equipped. We had ten railway cars. Four held our Red Army escort and their tracked all-terrain vehicles. We also had three sleepers, a galley car, and two flatcars piled high with rations, tents, excavators, Geiger counters, radios, and surveying instruments. Vlad brought a bulky calculating device, Captain Nina supplied her own mysterious crates, and I had a box of metallurgical analysis equipment, in case we found a piece of the UFO.

We were towed through Moscow under tight security, then our cars were shackled to the green-and-yellow Trans-Siberian Express.

Soon the expedition was chugging across the endless, featureless steppes of Central Asia. I grew so bored that I was forced to read Kazantsev’s book.

On June 30, 1908, a huge, mysterious fireball had smashed into the Tunguska River valley of the central Siberian uplands. This place was impossibly remote. Kazantsev suggested that the crash point had been chosen deliberately to avoid injuring Earthlings.

It was not until 1927 that the first expedition reached the crash site, revealing terrific devastation, but—no sign whatsoever of a meteorite! They found no impact crater, either; only the swampy Tunguska valley, surrounded by an elliptical blast pattern: sixty kilometers of dead, smashed trees.

Kazantsev pointed out that the facts suggested a nuclear airburst. Perhaps it was a deliberate detonation by aliens, to demonstrate atomic power to Earthlings. Or it might have been the accidental explosion of a nuclear starship drive. In an accidental crash, a socially advanced alien pilot would naturally guide his stricken craft to one of the planet’s “poles of uninhabitedness.” And eyewitness reports made it clear that the Tunguska body had definitely changed course in flight!

Once I had read this excellent work, my natural optimism surfaced again. Perhaps we would find something grand in Tunguska after all, something miraculous that the 1927 expedition had overlooked. Kulik’s expedition had missed it, but now we were in the atomic age. Or so we told ourselves. It seemed much more plausible on a train with two dozen other explorers, all eager for the great adventure.

It was an unsought vacation for us hardworking stukachi. Work had been savage throughout our departments, and we KGB had had a tough time keeping track of our comrades’ correctness. Meanwhile, back in Kaliningrad, they were still laboring away, while we relaxed in the dining saloon with pegged chessboards and tall brass samovars of steaming tea.

Vlad and I shared our own sleeping car. I forgave him for having involved me in this mess. We became friends again. This would be real man’s work, we told each other. Tramping through savage taiga with bears, wolves, and Siberian tigers! Hunting strange, possibly dangerous relics—relics that might change the very course of cosmic history! No more of this poring over blueprints and formulae like clerks! Neither of us had fought in the Great Patriotic War—I’d been too young, and Vlad had been in some camp or something. Other guys were always bragging about how they’d stormed this or shelled that or eaten shoe leather in Stalingrad—well, we’d soon be making them feel pretty small!

Day after day, the countryside rolled past. First, the endless, grassy steppes, then a dark wall of pine forest, broken by white-barked birches. Khrushchev’s Virgin Lands campaign was in full swing, and t

he radio was full of patriotic stuff about settling the wilderness. Every few hundred kilometers, especially by rivers, raw and ugly new towns had sprung up along the Trans-Sib line. Pre-fab apartment blocks, mud streets, cement trucks, and giant sooty power plants. Trains unloaded huge spools of black wire. “Electrification” was another big propaganda theme of 1958.

Our Trans-Sib train stopped often to take on passengers, but our long section was sealed under orders from Higher Circles. We had no chance to stretch our legs, and slowly all our carriages filled up with the reek of dirty clothes and endless cigarettes.

I was doing my best to keep Vlad’s spirits up when Nina Bogulyubova entered our carriage, ducking under a line of wet laundry. “Ah, Nina Igorovna,” I said, trying to keep things friendly. “Vlad and I were just discussing something. Exactly what does it take to merit burial in the Kremlin?”

“Oh, put a cork in it,” Bogulyubova said testily. “My money says your so-called spacecraft was just a chunk of ice and gas. Probably a piece of a comet which vaporized on impact. Maybe it’s worth a look, but that doesn’t mean I have to swallow crackpot pseudo-science!”

She sat on the bunk facing Vlad’s, where he sprawled out, stunned with boredom and strong cigarettes. Nina opened her briefcase. “Vladimir, I’ve developed those pictures I took of you.”

“Yeah?”

She produced a Kirlian photograph of his hand. “Look at these spiky flares of suppressed energy from your fingertips. Your aura has changed since we boarded the train.”

Vlad frowned. “I could do with a few deciliters of vodka, that’s all.”

She shook her head quickly, then smiled and blinked at him flirtatiously. “Vladimir Eduardovich, you’re a man of genius. You have strong, passionate drives …”

Vlad studied her for a moment, obviously weighing her dubious attractions against his extreme boredom. An affair with a woman who was his superior, and also KGB, would be grossly improper and risky. Vlad, naturally, caught my eye and winked. “Look, Nikita, take a hike for a while, okay?”

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

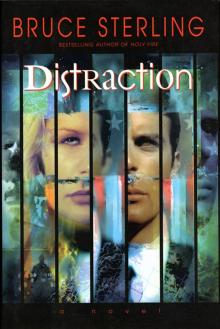

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase