- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus Read online

PRAISE FOR

BRUCE STERLING

* * *

AND

* * *

S C H I S M A T R I X P L U S

“A tsunami of imagination!”

—PHILIP JOSE FARMER

“If you want to know what the future might really be like, read Sterling.”

—GARDNER DOZOIS

“A powerful feat of sustained imagination, presenting a panoramic chunk of future history as broad and diverse as it is fast and furious…This is science fiction as it should be.”

— HARRINGTON J. BAYLEY,

AUTHOR OF THE GARMENTS OF CAEAN

“An author of dazzling range and insight. With Schismatrix, Bruce Sterling joins the ranks of those daring SF creators who invent futures of startling complexity.”

—LOCUS

“Crisp, colorful and superbly stimulating…Sterling is one of the best in the business!”

—BEST SELLERS

ACE BOOKS BY BRUCE STERLING

THE ARTIFICIAL KID

SCHISMATRIX

INVOLUTION OCEAN

MIRRORSHADES (Ed.)

CRYSTAL EXPRESS

ISLANDS IN THE NET

SCHISMATRIX PLUS

This Ace Book includes Schismatrix and selected stories

from Crystal Express. It has been completely reset in a

typeface designed for easy reading, and was

printed from new film.

SCHISMATRIX PLUS

An Ace Book / published by arrangement with the author

PRINTING HISTORY

Ace trade edition / December 1996

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1996 by Bruce Sterling.

Cover art by Danilo Ducak.

Book design by Maureen Troy.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part,

by mimeograph or any other means, without permission.

For information address: The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

The Putnam Berkley World Wide Web site address is:

http://www.berkley.com/berkley

Make sure to check out PB Plug, the science fiction/fantasy newsletter, at

http://www.pbplug.com

ISBN: 0-441-00370-2

ACE®

Ace Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group,

200 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016.

ACE and the “A” design are trademarks

belonging to Charter Communications, Inc.

PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Schismatrix, copyright © 1985 by Bruce Sterling; Arbor House hardcover edition, June 1985; Ace mass-market edition, June 1986.

“Swarm,” copyright © 1982 by Mercury Press, Inc., for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, April 1982.

“Spider Rose,” copyright © 1982 by Mercury Press, Inc., for The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1982.

“Cicada Queen,” copyright © 1983 by Terry Carr for Universe 13, edited by Terry Carr.

“Sunken Gardens,” copyright © 1984 by Omni Publications International, Ltd., for Omni, June 1984.

“Twenty Evocations,” copyright © 1984 by Bruce Sterling for Interzone, Spring 1984; first published as “Life in the Mechanist/Shaper Era: Twenty Evocations.”

CONTENTS

Introduction: The Circumsolar Frolics

SCHISMATRIX

Prologue

Part 1 - Sundog Zones

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Part 2 - Community and Anarchy

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Part 3 - Moving in Clades

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

SHAPER/MECHANIST STORIES

Swarm

Spider Rose

Cicada Queen

Sunken Gardens

Twenty Evocations

A SHAPER/MECHANIST CHRONOLOGY

Introduction:

The Circumsolar Frolics

I wrote this book, and these stories, eleven years ago. I finished the manuscript of SCHISMATRIX just before I turned thirty. Then I quit my day-job.

When I completed the Shaper/Mechanist series, I knew that I finally had a hot and sticky ten-fingered grip on the genre. I’d learned how to make science fiction address my own concerns, express my own ideas, and speak in my own voice. It was a hugely exciting feeling. I’ve never gotten over it. Also, I’ve never had a real job since.

This is the first book that I wrote on a word processor. My first two novels were written on manual typewriters. They were the best books I could do at the time, and they had quite a lot of rebellious kicking and thrashing in them, but they couldn’t be classed with SCHISMATRIX.

It was a revelation when I first saw my text become electric vapor on the screen of a computer. I realized that I’d become part of a new generation in science fiction, a generation that had profound, genuine, “technical” advantages over all our predecessors. This freed me almost overnight from any sense that I still dwelt in the long shadows of Verne, Wells, or Stapledon. Those writers were titans of the imagination, but they were one and all confined to analog technologies of ink and woodpulp. Now I could do what I liked with words—bend them, break them, jam them together, pick them apart again. It was like patiently studying blues guitar and suddenly finding a fire-engine-red Fender Stratocaster.

When I began work on the Shaper/Mechanist pieces, I had learned how to stop reading quite so much science fiction. By that time, I was already brimful. Instead, I learned to absorb the kind of material that science fiction professionals themselves like to read. Three books in particular had a huge influence on my thinking, and on the composition of the Shaper/Mechanist world.

First among them was THE WORLD, THE FLESH, AND THE DEVIL by J. D. Bernal. This book was written in the 1920s, and would be universally acknowledged as a stellar masterpiece of cosmic speculation, except for the uncomfortable fact that J. D. Bernal was a lifelong fervent Communist. His work simply couldn’t be metabolized during most of the twentieth century, because the author himself was politically unacceptable. I never had much use for Communism, but I had plenty of use for J. D. Bernal.

The second book was Freeman Dyson’s DISTURBING THE UNIVERSE. Freeman Dyson could have been a mighty figure in the genre if he’d become a science fiction writer instead of a mere world-class physicist at Princeton. I was lucky enough to have lunch with Freeman Dyson a couple of years ago. I was able to thank him for the fact that I had filed the serial numbers off his prose, hot-wired it and employed it in my work. Professor Dyson had never read SCHISMATRIX, but he was astonishingly good-humored about the fact that I had boldly hijacked thirty or forty of his ideas. What a gentleman and scholar!

The third book was Ilya Prigogine’s FROM BEING TO BECOMING. This book boasted some of the most awesomely beautiful scientific jargon that I had ever witnessed in print. The writing was of such dense, otherworldly majesty that it resembled Scripture. It was very like the “crammed Prose” and “eyeball kicks” that we cyberpunks were so enamored of, with the exception of course that Prigogine’s work was actual science and bore some coherent relation to consensus reality. So naturally I used his terminology as the basis for the Shaper/Mechanist mysticism. It worked like a charm. Eventually a fan of mine who happened to be one of Professor Prigogine’s students gave him a copy of CRYSTAL EXPRESS, which contained the Shaper/Mechanist short stories. Professor Prigogine remarked perceptively that these stories had

nothing whatever to do with his Nobel Prizewinning breakthroughs in physical chemistry. Well, that was very true, but charms are verbal structures. They work regardless of chemistry or physics.

I wrote the stories before the novel. I used the Shaper/Mechanist short stories as a method of exploration, a way to creep methodically into the burgeoning world of the book. First came “Swarm,” which involves two characters only, and is set light-years away from the eventual center of the action. Next I wrote “Spider Rose,” set on the fringes of the solar system, and the fringes of Schismatric society. After that came “Cicada Queen,” which thundered headlong into a major Shaper/Mechanist city and examined their society as it boiled like a technocrazed anthill. “Sunken Gardens” was set late in my future-history, a framing work. The experimental “Twenty Evocations” was my final word on the subject. It was a dry-run for the forthcoming novel, and with that effort, I was carrying my “crammed-prose” technique as far as it would go.

These were my first published short stories. I had one other story, “Man-Made Self,” published when I was a teenager; but alas, the manuscript pages were scrambled at the printer’s, and the published story was rendered unintelligible. I had to disown it. That made “Swarm” my official story premiere. “Swarm” was also my first magazine sale (to THE MAGAZINE OF FANTASY AND SCIENCE FICTION, in April 1982). “Swarm” is still the story of mine most often reprinted. I’m still fond of it: I can write a better prose now, but with that story, I finally gnawed my way through the insulation and got my teeth set into the buzzing copper wire.

SCHISMATRIX was my third novel, but the first to go into an immediate second-printing—in Japan. I’ve valued the Japanese SF milieu very highly ever since. Recently SCHISMATRIX became my first novel to come out in Finland. Perhaps there’s a quality in a good translation that can’t be captured with the original. One might not think that a book this weird and idiosyncratic could survive translation into non-Indo-European languages; but on the contrary, it’s that very weirdness that seems to push it through the verbal and cultural barriers. SCHISMATRIX is a creeping sea-urchin of a book—spikey and odd. It isn’t very elegant, and it lacks bilateral symmetry, but pieces of it break off inside people and stick with them for years.

These stories, and this novel, are the most “cyberpunk” works I will ever write. I wrote them in a fine fury of inspiration, in those halcyon days when me and my ratty little cyberpunk co-conspirators first saw our way clear into literary daylight. I think I could write another book as surprising as this one, or even as weird as this one; but it would no longer surprise people that I can be surprising. My audience would no longer find it weird to discover that I can be weird. When I wrote this book, I was surprising myself every day.

In those days of yore, cyberpunk wasn’t hype or genre history; it had no name at all. It hadn’t yet begun to be metabolized by anyone outside a small literary circle. But it was very real to me, as real as anything in my life, and when I was hip-deep into SCHISMATRIX chopping my way through circumsolar superpower conflicts and grimy, micro-nation terrorist space pirates, it felt like holy fire.

Now all the Shaper/Mechanist stuff is finally here in one set of covers. At last I can formally tell a skeptical public that the title of SCHISMATRIX is pronounced “Skiz-mat´-rix.” With a short a. Like “Schismatics,” but with an R. Also, SCHISMATRIX is spelled without a “Z.” I do hope this helps in future.

People are always asking me about—demanding from me even—more Shaper/Mechanist work. Sequels. A trilogy maybe. The Schismatrix sharecropping shared-universe “as created by” Bruce Sterling. But I don’t do that sort of thing. I never will. This is all there was, and all there is.

Bruce Sterling—[email protected]

Austin, Texas: 29-11-’95

Prologue

Painted aircraft flew through the core of the world. Lindsay stood in knee-high grass, staring upward to follow their flight.

Flimsy as kites, the pedal-driven ultralights dipped and soared through the free-fall zone, far overhead. Beyond them, across the diameter of the cylindrical world, the curving landscape glowed with the yellow of wheat and the speckled green of cotton fields.

Lindsay shaded his eyes against the sunlit glare from one of the world’s long windows. An aircraft, its wings elegantly stenciled in blue feathers on white fabric, crossed the bar of light and swooped silently above him. He saw the pilot’s long hair trailing as she pedaled back into a climb. Lindsay knew she had seen him. He wanted to shout, to wave frantically, but he was watched.

His jailers caught up with him: his wife and his uncle. The two old aristocrats walked with painful slowness. His uncle’s face was flushed; he had turned up his heart’s pacemaker. “You ran,” he said. “You ran!”

“I stretched my legs,” Lindsay said with bland defiance. “House arrest cramps me.”

His uncle peered upward to follow Lindsay’s gaze, shading his eyes with an age-spotted hand. The bird-painted aircraft now hovered over the Sours, a marshy spot in the agricultural panel where rot had set into the soil. “You’re watching the Sours, eh? Where your friend Constantine’s at work. They say he signals you from there.”

“Philip works with insects, Uncle. Not cryptography.”

Lindsay was lying. He depended on Constantine’s covert signals for news during his house arrest.

He and Constantine were political allies. When the crackdown came, Lindsay had been quarantined within the grounds of his family’s mansion. But Philip Constantine had irreplaceable ecological skills. He was still free, working in the Sours.

The long internment had pushed Lindsay to desperation. He was at his best among people, where his adroit diplomatic skills could shine. In isolation, he had lost weight: his high cheekbones stood out in sharp relief and his gray eyes had a sullen, vindictive glow. His sudden run had tousled his modishly curled black hair. He was tall and rangy, with the long chin and arched, expressive eyebrows of the Lindsay clan.

Lindsay’s wife, Alexandrina, took his arm. She was dressed fashionably, in a long pleated skirt and white medical tunic. Her pale, clear complexion showed health without vitality, as if her skin were a perfectly printed paper replica. Mummified kiss-curls adorned her forehead.

“You said you wouldn’t talk politics, James,” she told the older man. She looked up at Lindsay. “You’re pale, Abelard. He’s upset you.”

“Am I pale?” Lindsay said. He drew on his Shaper diplomatic training. Color seeped into his cheeks. He widened the dilation of his pupils and smiled with a gleam of teeth. His uncle stepped back, scowling.

Alexandrina leaned on Lindsay’s arm. “I wish you wouldn’t do that,” she told him. “It frightens me.” She was fifty years older than Lindsay and her knees had just been replaced. Her Mechanist teflon kneecaps still bothered her.

Lindsay shifted his bound volume of printout to his left hand. During his house arrest, he had translated the works of Shakespeare into modern circumsolar English. The elders of the Lindsay clan had encouraged him in this. His antiquarian hobbies, they thought, would distract him from plotting against the state.

To reward him, they were allowing him to present the work to the Museum. He had seized on the chance to briefly escape his house arrest.

The Museum was a hotbed of subversion. It was full of his friends. Preservationists, they called themselves. A reactionary youth movement, with a romantic attachment to the art and culture of the past. They had made the Museum their political stronghold.

Their world was the Mare Serenitatis Circumlunar Corporate Republic, a two-hundred-year-old artificial habitat orbiting the Earth’s Moon. As one of the oldest of humankind’s nation-states in space, it was a place of tradition, with the long habits of a settled culture.

But change had burst in, spreading from newer, stronger worlds in the Asteroid Belt and the Rings of Saturn. The Mechanist and Shaper superpowers had exported their war into this quiet city-state. The strain had split the population into factions: Lindsa

y’s Preservationists against the power of the Radical Old, rebellious plebes against the wealthy aristocracy.

Mechanist sympathizers held the edge in the Republic.

The Radical Old held power from within their governing hospitals. These ancient aristocrats, each well over a century old, were patched together with advanced Mechanist hardware, their lives extended with imported prosthetic technology. But the medical expenses were bankrupting the Republic. Their world was already deep in debt to the medical Mech cartels. The Republic would soon be a Mechanist client state.

But the Shapers used their own arsenals of temptation. Years earlier, they had trained and indoctrinated Lindsay and Constantine. Through these two friends, the leaders of their generation, the Shapers exploited the fury of the young, who saw their birthrights stolen for the profit of the Mechanists.

Tension had mounted within the Republic until a single gesture could set it off.

Life was the issue. And death would be the proof.

Lindsay’s uncle was winded. He touched his wrist monitor and turned down the beating of his heart. “No more stunts,” he said. “They’re waiting in the Museum.” He frowned. “Remember, no speeches. Use the prepared statement.”

Lindsay stared upward. The bird-painted ultralight went into a power dive.

“No!” Lindsay shouted. He threw his book aside and ran.

The ultralight smashed down in the grass outside the ringed stone seats of an open-air amphitheatre.

The aircraft lay crushed, its wings warped in a dainty convulsion of impact. “Vera!” Lindsay shouted.

He tugged her body from the flimsy wreckage. She was still breathing; blood gushed from her mouth and nostrils. Her ribs were broken. She was choking. He tore at the ring-shaped collar of her Preservationist suit. The wire of the collar cut his hands. The suit imitated space-suit design; its accordioned elbows were crushed and stained.

Little white moths were flying up from the long grass. They milled about as if drawn by the blood.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

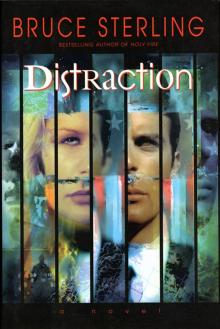

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase