- Home

- Bruce Sterling

War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Read online

War Is Virtual Hell

Bruce Sterling

Bruce Sterling

War Is Virtual Hell

The First Company of the 12th Armored Cavalry Regiment prepared for virtual battle.

At the Combined Arms and Tactical Training Center (CATTC) in Fort Knox, Ky., the troops prepared to enter SIMNET - a virtual war delivered via network links. With the almost Disney-like mimicry typical of SIMNET operations, the warriors were briefed in an actual field command-post, with folding camp-stools, fly swatters, and stenciled jerry cans. The young tankers wore green- and-brown forest camouflage fatigues, black combat boots, and forage caps.

Their command-post canvas tent was pitched inside the giant CATTC barn, right in the midst of silent rows of plastic tank simulators.

The Americans listened to a British officer on NATO exchange, Maj. Rogers, a two-year veteran of Fort Knox's simulator network. The major wore British olive- green, with rolled sleeves and gold-crowned epaulets and a Union Jack at the shoulder. He swiftly explained the tactical situation with deft scribbles on the plastic overlay covering a large topographical map.

Today's engagement would take place in a digital replica of California's Mojave Desert, the bleak, much-mangled terrain that is the heavy-armor stomping grounds of the US Army's National Training Center. Thanks to the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Defense Mapping Agency, and the Army's Topographic Engineering Center, the US military's vast Mojave acreage had been replicated virtually. The virtual Mojave is now available for daily use even in distant Fort Knox (and in an increasing number of other simulation centers around the planet).

The NTC's Mojave was a very harsh terrain, a hell of a place to lose a cow or to throw a tank track, and today it was worse yet, because it was swarming with the Opposing Forces.

The Threat were on their way in overwhelming numbers. Their assault force was four times larger than the beleaguered Americans, and they were blitzkrieging headlong in Soviet T-72 heavy tanks and mechanized transports.

The unlucky One-Twelve Cav were to take their initial stand in the ruggedly digitized Mojave hills on a baseline code-named Purple. Their orders were to fight in their sector, delaying the advance as best they could, while retreating in good order to Baseline Amber, where the survivors (if there were any) were to take another stand.

The attacking enemy would advance from west to east. That much was already known. But the exact enemy tactics were obscured by the fog of war.

The US company commander, Capt. Van Aken, studied the terrain and deployed his meager forces with care. Alpha Platoon to guard the center. Bravo Platoon to the north. Charlie Platoon to the south. The command post to the rear, near Baseline Amber. And the scouts, in their swift but lightly armored Bradleys, to range ahead of Baseline Purple.

The One-Twelve Cav had their orders. They understood their strategy. They left the command post for the squat plastic ranks of simulators. The Jacuzzis of Death.

From the outside, a SIMNET M1 Abrams tank simulator is clearly not a tank. It looks like an oddly humped gray fiberglass shower-stall. The simulator is, in fact, built by Jacuzzi from the same materials as a whirlpool bath. Its interior, however, is designed to psycho-logically replicate the basic tank experience, and it does.

Inside, the simulator is the proper shape and size for a tank's crew chamber. It makes all the proper sounds: the loud engine whine, the ominous rumble of treads, the multi-ton coffee-grinder racket as the turret slews, the concussive thud of the main gun firing. It has the instruments of a tank, though many of those controls are nonfunctional and only painted-on. There are no actual 40- pound high-explosive shells inside simulators, though the loader, by design, must still go through the physical motions of cramming them into the cannon, with all the proper timing, proper footwork, and the proper clanks and thuds.

A real M1 Abrams battle tank is a nightmarish vehicle. It weighs 70 tons. It's 26 feet long and 12 feet wide. It carries a 120-millimeter cannon that fires rounds that travel a mile-per-second: high-explosive shells, or armor-piercing uranium slugs. The M1 tank can climb obstacles three feet high with no trouble, cross ditches eight feet wide with ease, and roar down roads at 42 mph. It is an extremely lethal and frightening machine that can kill anything it can see.

It is also a horrible place in which to die. The Abrams holds four men. Three of them (the tank commander, the gunner, and the loader) ride in the crew chamber which is about the size of a large bedroom closet. The tank commander sits on a swivel-seat with his knees at the upper back of the gunner, who is crammed into a tiny ergonomic nook. The loader heaves shells into the butt of the 120- millimeter cannon, which juts like a dinosaur's rump into the turret cavity. The fourth man, the driver, lies on his back in a padded niche much the size and shape of a coffin. He steers the tank with a pivoting pair of black rubber handles from a metal post over his belly. He is not inside the turret with the other men; instead, he is squirreled away into the bowels of the machine and communicates by headset. Like the commander and the gunner, the driver's view of the world comes through "vision blocks," three rectangular blocks each the size and shape of a rear-view mirror.

Almost every visible surface within the chamber is covered with readout screens, switches, sensors, gauges, and maintenance monitors. The area around the tank commander's tall black stool has a weirdly shaped black joystick, a targeting scope, and two flat screens with buttons bearing cryptic acronyms. These big square buttons are designed to be pressed by hands encased in chemical-warfare gauntlets. They're like a lethal parody of the child-sized buttons on a My First Sony.

Tanks are, of course, very well-armored vehicles, but there is very little on earth that can resist a 120-millimeter uranium slug traveling at a mile-per- second. Anything hit by this projectile instantly buckles and splatters. Modern tank-to-tank warfare is extremely lethal and the exchange of direct fire generally lasts only seconds.

Those seconds are precious, so time spent inside a simulator is not a picnic. Simulators are not toys. They are "fun" in some sense, but only about as much fun as an actual no-kidding tank. You can drive these simulators across cyberspace landscapes, coordinate their tactics, advance and retreat, aim their cannon, fire and be fired upon. You can smash into obstacles, bog down in mud, fall off cliff edges, and experience various kinds of simulated mechanical and engine trouble. You can panic, you can screw up, you can make a fool of yourself in front of your comrades and your commander. You can directly affect your real- life military career through what you do in simulators. And you can be killed inside simulators - virtually speaking.

The One-Twelve Cav deployed to their virtual tanks, opened the thick plastic doors on their hefty refrigerator-style hinges, took their posts at the black plastic seats, and were sealed inside. The drivers were also formally encased in their own separate plastic sarcophagi.

They started their virtual engines. They began exchanging virtual radio traffic. They examined their virtual navigation, and squinted at the desert-colored polygons in their vision-blocks. From the Ethernet lines dangling from metal frames overhead, SIMNET packets began to flow to and from the gloss-black Computer Image Generators, and the SIMNET recording angel, the big network machine they called "Radcliff," started to monitor the battle.

In another area of the simulator barn, the wily Threat commander brooded over his color Macintosh. Capt. Baker, a US Marine tactical instructor on loan to Fort Knox, was taking on the entire American force single-handedly. The Yankee opposition were sealed inside their simulators, gazing nervously at the pixelated desert and jockeying for position. But Baker could see the entire landscape at a glance. His on-screen map showed red roads, yellow badlands, the milling icons of the blue Friendlies,

and the red lozenges of his own approaching Threat task force, rumbling forward west of Baseline Purple.

Capt. Baker followed Soviet tactical doctrine scrupulously. He gave his unmanned, computer-generated tanks and armored vehicles their instructions with deft points-drags-and-clicks of his Macintosh mouse.

His strategy was to spot or create a weakness in the Yankee defenses, pour as much of his armor through the chink as possible, then roll at blitzkrieg speed to a target deep behind enemy lines: "Objective Kiev."

Capt. Baker coolly sent three groups of digital scouts to certain death.

In the north, Bravo Platoon was the first to spot the approaching enemy scouts. Three Bravo tanks lurched suddenly from ambush and blasted the mechanized transports into smoking digital wreckage. The dying transports took a posthumous vengeance, though, by calling in an artillery bombardment on the Yankee position. Bravo Platoon saw red and yellow impacts spike their hillside landscape, and a vicious crump of high explosives burst from the Perceptronics audio simulators.

A second enemy probe tried the center of the American line. Alpha Platoon called in a hasty artillery strike of their own against the enemy reconnaissance. Unfortunately, the map coordinates were badly garbled in the growing excitement. Lethal "friendly fire" now whumped and blasted around Alpha Platoon's own scouts. One scout was killed by an enemy transport; the other shot dead by friendly tanks as it fled into the trigger-happy muzzles of its own backup units.

By now the radio traffic was going wild. Back at the SIMNET system operator's omniscient "Stealth Station," every howl and yelp was spooling onto a cheap K- Mart boombox for later analysis by trainers.

Under the stress of battle, the American chain of command was disintegrating, and the engagement was becoming a wild scrap.

But one Alpha tank survived. He had found a slope of ground in a sharp declivity, a sniper's paradise. Inside the simulator, the tank commander of Alpha Unit 24 began to lacerate the enemy column, rolling back behind the safety of the virtual ridge, reloading his cannon, then surging up again to swiftly nail another victim with his laser target reticule. It is a terrible thing to snipe with a laser-guided 120-mm cannon. Alpha 24 was methodically tearing the enemy column apart. Within some 30 seconds four enemy vehicles were reduced to burning hulks.

The robotic enemy column seemed stunned by Alpha 24's lethal jack-in-the-box tactic. They milled around in confusion, unable to get a clear shot. Then the American artillery kicked in, bracketing the column in lethal fire. With their position absolutely untenable, the column charged the sniping tank. Alpha 24 killed two more tanks before being outflanked and forced to retreat.

Bravo Platoon was standing firm in the north, but it had been outfoxed. No one was coming their way. Instead, two more enemy columns suddenly appeared in the far south, in Charlie Platoon's turf. Seen through the Threat commander's Macintosh map, the jittering red icons resembled angry ants.

Charlie Platoon as a whole was caught unawares. Despite their wire-guided TOW missiles, Charlie Platoon's Bradley Fighting Vehicles were no match for the Threat heavy armor. Charlie Platoon was swiftly overwhelmed, howling through the radio network for backup that was too slow, and too far away.

Charlie Platoon's survivors called in air-support as they struggled to reach the relative safety of Baseline Amber. In answer, two automatic Apache attack helicopters emerged from the blue nothingness of SIMNET's cyberspace sky. They fired air-to-surface missiles and swiftly roasted a pair of enemy tanks; but the other T-72 tanks potted both the choppers on the wing. The Apaches fell in crumpled digital heaps of flaming polygons.

As the engagement proceeded, dead men began to show up in the CATTC video classroom. Inside the simulators, their vision blocks had gone suddenly blank with the onset of virtual death. Here in CATTC's virtual Valhalla, however, a large Electrohome video display unit showed a comprehensive overhead map of the entire battlefield. Group by group, the dead tank crews filed into the classroom and gazed upon the battlefield from a heavenly perspective.

Slouching in their seats and perching their forage caps on their knees, they began to talk. They weren't talking about pixels, polygons, baud-rates, Ethernet lines, or network architecture. If they'd felt any gosh-wow respect for these high-tech aspects of their experience, those perceptions had clearly vanished early on. They were talking exclusively about fields of fire, and fall-back positions, and radio traffic and indirect artillery strikes. They weren't discussing "virtual reality" or anything akin to it. These soldiers were talking war.

"Get them, sir," a deceased tanker muttered vengefully as he watched Alpha 24's heroic stand in the fake Mojave Hills. Another tanker, from the Alpha scout unit, griped bitterly about his death by friendly fire: "fratricide." Dying at the hands of his own platoon had been especially cruel. It was clear that the real-life lesson of unit coordination had sunk in well - at least for this poor guy.

"It's only SIMNET," another tanker told him at last. "You're not bleeding."

They weren't bleeding. That was undeniable. On the contrary, they'd just been killed in combat, yet also had the amazing luxury to learn by this experience. The CATTC trainers called off the battle in time for lunch; the result was now a foregone conclusion. As Capt. Baker explained to his virtual enemies and real- life students, "There'll be hot borscht and vodka at Objective Kiev tonight." The dead soldiers, and the few pleased survivors, had shakes, fries and burgers from the local Burger King.

When they returned from their lunch, Maj. Rogers replayed the battle for them, hitting the high points with detailed graphics from the big machine called Radcliff. Any event can be scrutinized, from any angle of vision, at any moment in time that the trainers desired.

Virtual Reality as a Strategic Asset

SIMNET today is a clunky and rapidly aging mid-1980s technology; its giant, $100,000 image generators are so large that they bear red adhesive labels: "WARNING: RISK OF PERSONAL INJURY FROM RACK TIPPING FORWARD." SIMNET still thrives in everyday use at Fort Knox, Fort Rucker, Fort Denning and a number of other sites, sometimes linked together through long-distance lines, more often not. But better stuff is coming: faster, cheaper, more sophisticated, and far better-connected.

The people at the Institute for Defense Analyses know all this. The Institute is a large, brown, campus-like building set in a pleasant wooded lot outside the Beltway of Washington, D.C. Its tall brick walls are festooned with white security telecameras. White shuttle-vans with the IDA logo - an infinity-sign in a triangle with the IDA acronym - pull up periodically, disgorging small scholarly groups of tweed-jacketed military-academic spooks.

I visited the Institute last fall. Groups of Air Force bluesuiters ambled periodically into the "Stealth Room." "Stealth technology" cloaks observers in digital invisibility, so that they can travel to any point inside a simulated battle. A huge triptych of full-color computer screens showed the simulated activity of a certain weapons system I was forbidden to identify publicly. The tarpaulin-shrouded chambers within the Institute were draped with wrist-thick clusters of black cabling leading to Sun workstations, networked Macintoshes, and a variety of prototype simulators. Everything hummed.

Col. Jack A. Thorpe, USAF, Ph.D., spends a lot of time in the Institute. Col. Thorpe is the "Father of Distributed Simulation" and is America's foremost advocate of virtual reality as a strategic asset.

The Colonel wore a civilian pinstriped suit, an understated maroon tie, and polished black wingtips. Col. (or Doctor) Thorpe is a cognitive psychologist specializing in training techniques; he is tall and lean and bespectacled, with a straight nose, dark hair, and hollow temples, and he possesses the vigorous air of a man with a vision and clear ideas of how to get there. He is somewhere near his early forties.

Col. Thorpe's highly unusual expertise makes his position in the military hierarchy somewhat anomalous. He is a career Air Force officer who nevertheless pioneered virtual reality networks for the US Army. He is also the special assistant for simulations at DARPA. He

clearly has a lot of pull at the Institute for Defense Analyses, his institutional home away from home, where DARPA sponsors the IDA Advanced Distributed Simulation Laboratory.

Col. Thorpe also has a number of friends among the computer-networking experts at the University of Central Florida in Orlando, and more colleagues yet at the Defense Mapping Agency, and yet more in the Topographic Engineering Center, and plenty of eager listeners from all over the defense-contracting industry.

And yet Col. Thorpe's primary role in today's USmilitary is as "Leader of Thrust Six" for the Director of Defense Research and Engineering.

Dr. Victor Reis, Col. Thorpe's immediate superior, is Director of Defense Research and Engineering. Dr. Reis has a seven-point plan for distributing $3 billion worth of defense research in fiscal year 1993. The plan involves fairly standard post-Cold War matters such as global surveillance, air superiority, precision strikes, and advanced land combat. But the sixth point in the Reis plan is "Synthetic Environments."

Col. Thorpe is the premier Defense Department evangelist for synthetic environments. His interest in these matters goes back to the late '70s, when he was in the Air Force Office of Scientific Research. In those days, full-scale Air Force jet simulators cost $40 million each. The simulators - odd devices that perch on hydraulic stilts and pitch and toss their wannabe-ace occupants like broncos - clearly worked well in flight-training, but they were clumsy and they cost far too much, and worst of all, they were not connected.

Col. Thorpe is a connectivity visionary first and foremost.

His reasoning is simple but profound. An army is not an armed mob of heroic individualists. An army is a connected, coordinated, disciplined killing force, working systematically in close cooperation to a desired end. In any stand-up fight, an army will destroy a mob, even an armed and heroic mob, with very little trouble.

There are two basic problems with isolated simulators. They don't connect to other soldiers, and they don't connect to an enemy. They might train individual pilots how to fly very well, but they can't train squadrons how to fight. They can teach the skill of handling an aircraft, but they can't teach combat with your own comrades at hand, against an intelligent enemy who can see you and react to what you do. Similarly, a single tank simulator might train a single crew to some brilliant pitch of mechanical efficiency, but it can't build platoons, companies, battalions, or regiments of armor that can work together, confront enemies, and conquer the battlefield. Armies win wars, not lone heroes. In real wars, Rambos die quick.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

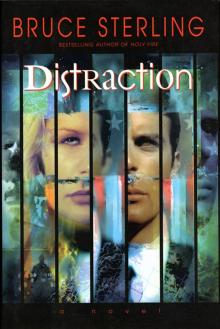

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase