- Home

- Bruce Sterling

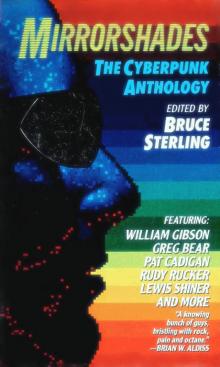

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology Read online

BRAVE NEW WORLD OF CYBERPUNK

“A wild and potent collection by some of the brightest new writers in science fiction, mixing technology with desire, flashing futures within a starred mirror.”

—Roger Zelazny

". . . filled with surreal visionary intensity. They are often sexy, occasionally lewd, always frightening, are filled with black humor, obsessed with the interface of high-tech and pop underground, and always fascinating.”

—Fantasy Review

“A good lively collection.”

—Publishers Weekly

“The hip, musically literate high-tech movement known as ‘cyberpunk’ has rocked the once-nerdy precincts of ‘hard’ science fiction... Raymond Chandler on uppers.”

—The Village Voice

“Cyberpunks thrive in a niche where high-tech and high-literature interface. They write hard-edged macrofiction that is ripe with ideas, gracefully written and appropriate to this age of instantaneous global communication and babies whelped in petri dishes.”

—Wall Street Journal

“The high-tech language and experimental styles of Greg Bear, William Gibson and other new wave writers provide a kaleidoscopic vision of tomorrow’s brave new world.”

—Library Journal

CONTENTS

Title Page

Copyright

Acknowledgements

Preface

THE GERNSBACK CONTINUUM

by William Gibson

SNAKE EYES

by Tom Maddox

ROCK ON

by Pat Cadigan

TALES OF HOUDINI

by Rudy Rucker

400 BOYS

by Marc Laidlawn

SOLSTICE

by James Patrick Kelly

PETRA

by Greg Bear

TILL HUMAN VOICES WAKE US

by Lewis Shiner

FREEZONE

by John Shirley

STONE LIVES

by Paul Di Filippo

RED STAR, WINTER ORBIT

by Bruce Sterling and William Gibson

MOZART IN MIRRORSHADES

by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shinern

Extra: Freezone (Original by “ROCK ON”)

by John Shirley

This Ace Book contains the complete text of the original edition.

MIRRORSHADES

An Ace Book / published by arrangement with Arbor House Publishing Company

PRINTING HISTORY

Arbor House edition / December 1986 Ace edition / July 1988

All rights reserved.

Copyright © 1986 by Bruce Sterling.

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information address: Arbor House Publishing Company, 235 E. 45th St., New York, N. Y. 10017.

ISBN: 0-441-53382-5

Ace Books are published by The Berkley Publishing Group, 200 Madison Avenue, New York, N. Y. 10016.

The name “ACE” and the “A” logo are trademarks belonging to Charter Communications, Inc.

This eBook is based on the 1998 ACE edition.

However, all stories in this eBook don't correspond exactly with the versions found in the 1988 edition as they have undergone modifications by their respective editors over the years.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

For the 1988 ACE edition

“The Gernsback Continuum” by William Gibson. Copyright © 1981 by Terry Carr. First published in Universe 11. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Snake-Eyes” by Tom Maddox. Copyright © 1986 by Omni Publications International Ltd. First published in Omni April 1986. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Rock On” by Pat Cadigan. Copyright © 1984 by Pat Cadigan. First published in Light Years and Dark (Berkley). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Tales of Houdini” by Rudy Rucker. Copyright © 1983 by Rudy Rucker. First published in Elsewhere (Ace). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“400 Boys” by Marc Laidlaw. Copyright © 1983 by Omni Publications International Ltd. First published in Omni, November 1983. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Solstice” by James Patrick Kelly. Copyright © 1985 by Davis Publications, Inc. First published in Isaac Asimov's Science Fiction Magazine, June 1985. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Petra” by Greg Bear. Copyright © 1982 by Greg Bear. First published in Omni, February 1982. Reprinted by permission of the author.

‘Till Human Voices Wake Us” by Lewis Shiner. Copyright © 1984 by Mercury Press, Inc. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1984. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Freezone” by John Shirley. Copyright © 1985 by John Shirley. First published in Eclipse (Bluejay). Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Stone Lives” by Paul Di Filippo. Copyright © 1985 by Mercury Press, Inc. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1985. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Red Star, Winter Orbit” by Bruce Sterling and William Gibson. Copyright © 1983 by Omni Publications International Ltd. First published in Omni, July 1983. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

“Mozart in Mirrorshades” by Bruce Sterling and Lewis Shiner. Copyright © 1985 by Omni Publications International Ltd. First published in Omni, September 1985. Reprinted by permission of the authors.

For the 2016 eBook edition

“The Gernsback Continuum” first appeared in Universe 11, © 1981 by Terry Carr.

“Freezone”* extracted from Eclipse, Copyright © 2012 by John Shirley.

“Freezone” by John Shirley © 1986, 2012 John Shirley. First publication, original version: Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology, ed. Bruce Sterling (Berkley). This version: original by “ROCK ON” Copyright © 2012 by Paula Guran.

“Snake Eyes” by Tom Maddox is released under a Creative Commons License: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nd-nc/1.0/

“Rock On,” by Pat Cadigan. Copyright © 1984 by Pat Cadigan. First published in Light Years And Dark (Berkley).

“Tales of Houdini” appears in Complete Stories Copyright © 2016 Rudy Rucker

“400 Boys” copyright 1983 by Marc Laidlaw. First appeared in Omni Magazine, November 1983.

“Solstice,” by James Patrick Kelly. Copyright © 1985 by Davis Publications, Inc. First published in Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction Magazine, June 1985. Reprinted by permission of the author.

“Petra” Copyright © 2004 by Greg Bear, “Petra” copyright © 1981 by Omni Publications International, Ltd. for Omni.

“Till Human Voices Wake Us” © 1984 by Mercury Press, Inc. First published in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, May 1984. Some rights reserved.

“Stone Lives” first appeared in The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in 1985.

‘Red Star, Winter Orbit’; © by Omni Publications International Ltd, 1983. Appears in Burning Chrome, Copyright © William Gibson 1986.

“Mozart in Mirrorshades” is © 1985 by Omni Publications International Ltd. First published in Omni, September, 1985.

PREFACE

This book showcases writers who have come to prominence within this decade. Their allegiance to Eighties culture has marked them as a group—as a new movement in science fiction.

This movement was quickly recognized and given many labels: Radical Hard SF, the Outlaw Technologists, the Eighties Wave, the Neuromantics, the Mirrorshades Group.

But of all the labels pasted on and peeled throughout the early Eighties, one has stuck: cyberpunk.

&nbs

p; Scarcely any writer is happy about labels—especially one with the peculiar ring of "cyberpunk." Literary tags carry an odd kind of double obnoxiousness: those with a label feel pigeonholed; those without feel neglected. And, somehow, group labels never quite fit the individual, giving rise to an abiding itchiness. It follows, then, that the "typical cyberpunk writer" does not exist; this person is only a Platonic fiction. For the rest of us, our label is an uneasy bed of Procrustes, where fiendish critics wait to lop and stretch us to fit.

Yet it's possible to make broad statements about cyberpunk and to establish its identifying traits. I'll be doing this too in a moment, for the temptation is far too strong to resist. Critics, myself included, persist in label-mongering, despite all warnings; we must, because it's a valid source of insight—as well as great fun.

Within this book, I hope to present a full overview of the cyberpunk movement, including its early rumblings and the current state of the art. Mirrorshades should give readers new to Movement writing a broad introduction to cyberpunk's tenets themes, and topics. To my mind, these are showcase stories. strong, characteristic examples of each writer's work to date. I've avoided stories widely anthologized elsewhere, so even hardened devotees should find new visions here.

Cyberpunk is a product of the Eighties milieu—in some sense, as I hope to show later, a definitive product. But its roots are deeply sunk in the sixty-year tradition of modem popular SF.

The cyberpunks as a group are steeped in the lore and tradition of the SF field. Their precursors are legion. Individual cyberpunk writers differ in their literary debts; but some older writers, ancestral cyberpunks perhaps, show a clear and striking influence.

From the New Wave: the streetwise edginess of Harlan Ellison. The visionary shimmer of Samuel Delany. The free-wheeling zaniness of Norman Spinrad and the rock esthetic of Michael Moorcock; the intellectual daring of Brian Aldiss; and, always, J. G. Ballard.

From the harder tradition: the cosmic outlook of Olaf Stapledon; the science/politics of H. G. Wells; the steely extrapolation of Larry Niven, Poul Anderson, and Robert Heinlein.

And the cyberpunks treasure a special fondness for SF's native visionaries: the bubbling inventiveness of Philip Jose Farmer; the brio of John Varley, the reality games of Philip K. Dick; the soaring, skipping beatnik tech of Alfred Bester. With a special admiration for a writer whose integration of technology and literature stands unsurpassed: Thomas Pynchon.

Throughout the Sixties and Seventies, the impact of SF's last designated "movement," the New Wave, brought a new concern for literary craftsmanship to SF. Many of the cyberpunks write a quite accomplished and graceful prose; they are in love with style, and are (some say) fashion-conscious to a fault. But, like the punks of '77, they prize their garage-band esthetic. They love to grapple with the raw core of SF: its ideas. This links them strongly to the classic SF tradition. Some critics opine that cyberpunk is disentangling SF from mainstream influence, much as punk stripped rock and roll of the symphonic elegances of Seventies "progressive rock." (And others—hard- line SF traditionalists with a firm distrust of "artiness"—loudly disagree.)

Like punk music, cyberpunk is in some sense a return to roots. The cyberpunks are perhaps the first SF generation to grow up not only within the literary tradition of science fiction but in a truly science-fictional world. For them, the techniques of classical "hard SF"—extrapolation, technological literacy—are not just literary tools but an aid to daily life. They are a means of understanding, and highly valued.

In pop culture, practice comes first; theory follows limping in its tracks. Before the era of labels, cyberpunk was simply "the Movement"—a loose generational nexus of ambitious young writers, who swapped letters, manuscripts, ideas, glowing praise, and blistering criticism. These writers—Gibson, Rucker Shiner, Shirley, Sterling—found a friendly unity in their common outlook, common themes, even in certain oddly common symbols, which seemed to crop up in their work with a life of their own. Mirrorshades, for instance.

Mirrored sunglasses have been a Movement totem since the early days of '82. The reasons for this are not hard to grasp. By hiding the eyes, mirrorshades prevent the forces of normalcy from realizing that one is crazed and possibly dangerous. They are the symbol of the sunstaring visionary, the biker, the rocker, the policeman, and similar outlaws. Mirrorshades—preferably in chrome and matte black, the Movement's totem colors—appeared in story after story, as a kind of literary badge.

These proto-cyberpunks were briefly dubbed the Mirrorshades Group. Thus, this anthology's title, a well-deserved homage to a Movement icon. But other young writers, of equal talent and ambition, were soon producing work that linked them unmistakably to the new SF. They were independent explorers, whose work reflected something inherent in the decade, in the spirit of the times. Something loose in the 1980s.

Thus, "cyberpunk"—a label none of them chose. But the term now seems a fait accompli, and there is a certain justice in it. The term captures something crucial to the work of these writers, something crucial to the decade as a whole: a new kind of integration. The overlapping of worlds that were formerly separate: the realm of high tech, and the modern pop under- ground.

This integration has become our decade's crucial source of cultural energy. The work of the cyberpunks is paralleled throughout the Eighties pop culture: in rock video; in the hacker underground; in the jarring street tech of hip-hop and scratch music; in the synthesizer rock of London and Tokyo. This phenomenon, this dynamic, has a global range; cyberpunk is its literary incarnation.

In another era this combination might have seemed far-fetched and artificial. Traditionally there has been a yawning cultural gulf between the sciences and the humanities: a gulf between literary culture, the formal world of art and politics. and the culture of science, the world of engineering and industry.

But the gap is crumbling in unexpected fashion. Technical culture has gotten out of hand. The advances of the sciences are so deeply radical, so disturbing, upsetting, and revolutionary, that they can no longer be contained. They are surging into culture at large; they are invasive; they are everywhere. The traditional power structure, the traditional institutions, have lost control of the pace of change.

And suddenly a new alliance is becoming evident: an integration of technology and the Eighties counterculture. An un-holy alliance of the technical world and the world of organized dissent—the underground world of pop culture, visionary fluidity, and street-level anarchy.

The counterculture of the 1960s was rural, romanticized, anti-science, anti-tech. But there was always a lurking contradiction at its heart, symbolized by the electric guitar. Rock technology was the thin edge of the wedge. As the years have passed, rock tech has grown ever more accomplished, expanding into high-tech recording, satellite video, and computer graphics. Slowly it is turning rebel pop culture inside out, until the artists at pop's cutting edge are now, quite often, cutting-edge technicians in the bargain. They are special effects wizards, mixmasters, tape-effects techs, graphics hackers, emerging through new media to dazzle society with head-trip extravaganzas like FX cinema and the global Live Aid benefit. The contradiction has become an integration.

And now that technology has reached a fever pitch, its influence has slipped control and reached street level. As Alvin Toffler pointed out in The Third Wave—a bible to many cyberpunks—the technical revolution reshaping our society is based not in hierarchy but in decentralization, not in rigidity but in fluidity.

The hacker and the rocker are this decade's pop-culture idols, and cyberpunk is very much a pop phenomenon: spontaneous, energetic, close to its roots. Cyberpunk comes from the realm where the computer hacker and the rocker overlap, a cultural Petri dish where writhing gene lines splice. Some find the results bizarre, even monstrous; for others this integration is a powerful source of hope.

Science fiction—at least according to its official dogma—has always been about the impact of technology. Bu

t times have changed since the comfortable era of Hugo Gernsback, when Science was safely enshrined—and confined—in an ivory tower. The careless technophilia of those days belongs to a vanished, sluggish era, when authority still had a comfortable margin of control.

For the cyberpunks, by stark contrast, technology is visceral. It is not the bottled genie of remote Big Science boffins; it is pervasive, utterly intimate. Not outside us, but next to us. Under our skin; often, inside our minds.

Technology itself has changed. Not for us the giant steam- snorting wonders of the past: the Hoover Dam, the Empire State Building, the nuclear power plant. Eighties tech sticks to the skin, responds to the touch: the personal computer, the Sony Walkman, the portable telephone, the soft contact lens.

Certain central themes spring up repeatedly in cyberpunk. The theme of body invasion: prosthetic limbs, implanted circuitry, cosmetic surgery, genetic alteration. The even more powerful theme of mind invasion: brain-computer interfaces, artificial intelligence, neurochemistry—techniques radically redefining - the nature of humanity, the nature of the self.

As Norman Spinrad pointed out in his essay on cyberpunk, many drugs, like rock and roll, are definitive high-tech products. No counterculture Earth Mother gave us lysergic acid - it came from a Sandoz lab, and when it escaped it ran through society like wildfire. It is not for nothing that Timothy Leary proclaimed personal computers "the LSD of the 1980s"—these are both technologies of frighteningly radical potential. And, as such, they are constant points of reference for cyberpunk.

The cyberpunks, being hybrids themselves, are fascinated by interzones: the areas where, in the words of William Gibson, "the street finds its own uses for things." Roiling, irrepressible street graffiti from that classic industrial artifact, the spray can. e subversive potential of the home printer and the photocopier. Scratch music, whose ghetto innovators turn the phonograph itself into an instrument, producing an archetypal Eighties music where funk meets the Burroughs cut-up method. "It's all in the mix"—this is true of much Eighties art and is as applicable to cyberpunk as it is to punk mix-and-match retro fashion and multitrack digital recording.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase