- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Ascendancies

Ascendancies Read online

Ascendancies

The Best of Bruce Sterling

Bruce Sterling

Contents

Introduction by Karen Joy Fowler

Foreword by Bruce Sterling

Part I: The Shaper/Mechanist Stories

Swarm

Spider Rose

Cicada Queen

Sunken Gardens

Twenty Evocations

Part II: Early Science Fiction and Fantasy

Green Days in Brunei

Dinner in Audoghast

The Compassionate, the Digital

Flowers of Edo

The Little Magic Shop

Our Neural Chernobyl

We See Things Differently

Dori Bangs

Part III: The Leggy Starlitz Stories

Hollywood Kremlin

Are You for 86?

The Littlest Jackal

Part IV: The Chattanooga Stories

Deep Eddy

Bicycle Repairman

Taklamakan

Part V: Later Science Fiction and Fantasy

The Sword of Damocles

Maneki Neko

In Paradise

The Blemmye’s Strategem

Kiosk

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Introduction

by Karen Joy Fowler

My very first conversation with Bruce Sterling was about mass outbreaks of hysterical dancing. One of us was shockingly well-informed. Other topics we have discussed over the years: the Fox sisters and their toe-cracking séances, the aboriginal inhabitants of what is now Texas, the writings of Lafcadio Hearn plus the modern Japanese response to the ‘Anne of Green Gables’ books (the one subject leading inevitably to the other), Sasquatch sightings in the Washington territories, cyclical patterns in Chinese politics, feudal messianic movements. If the list trends (it does) toward my own interests and obsessions, this is because one of us is shockingly polite. There may be a subject Sterling cannot discuss with ease and erudition, but I haven’t found it yet. Nor will you.

What I notice first about this new collection is the two groups of linked stories. The Shaper/Mechanist grouping is set in the far future. The place is space. These stories constitute some of Sterling’s earlier work. The second group takes place in the near future and right here at home—Europe, Japan, Chattanooga, etc. This second group was written later but they happen earlier. It’s just like the two Star Wars trilogies. This makes them tricky to talk about.

The protagonists of the first set, which is the last set, are barely human or not at all so. They have names like Spider Rose. The protagonists of the second set, which is the first set, are completely human. They have names like Spider Pete. Leggy Starlitz. Deep Eddy. The females in the near future are trained, armed, and earnest. The females in the far future are bulbous and have many eyes. What strikes me is how within the linked stories Sterling’s tone is consistent, but from the first group to the second has changed completely.

The Shaper/Mechanist work is serious, even apocalyptic. The landscapes are grim and the plots grimmer. In contrast, the tone of the near future stories is detached and witty. Sterling is having fun and has chosen to do so conspicuously. This is true of his sentences as well as his plots. He’s not the only one having fun. Sentences like “[double entendres] rose to his lips like drool from the id,” certainly improve my mood. So do phrases like “Pamyat rightism with a mystical pan-Slavic spin” and “autonomous self-assembly proteinaceous biotech,” at least when, like this, they’re tossed about like confetti. A juggler appears briefly, wearing smart gloves, flinging “lit torches in flaming arcs three stories high.” A dead soldier we’ll never see again is described as having “come down from the heavens…a leaping, brick-busting, lightning-spewing exoskeleton, all acronyms and input jacks.” Things are “fast, cheap, and out of control.”

Europe may teem with terrorists—some of them Finnish nationalists, some of them devout Islamists, some of them Irish soccer fans. The web may have compiled Orwellian dossiers accessible to anyone with a bit of tech and a tolerance for burnt eyelids. The Chinese may be burying inconvenient ethnicities underground and pretending it’s space travel. But Sterling is too interested in it all to be gloomy. It’s not all bad news, of course. Gene-spliced ticks dispense athletic performance enhancers. You store them in your armpits!

His protagonists are just as unflappable as he is. The near future Sterling hero is nimble, fluent in the language of the moment, even-tempered even in defeat (though feminists do seem to make Leggy surly.) Most of all, this protagonist tends to be lucky. He’s not himself an activist, though he’s surrounded by them (and they don’t look good)—idealists, terrorists, capitalists, sociologists, and all of them agents of mayhem. Inside the chaos, the Sterling hero looks for a niche, an angle, an obsession. His goals tend to be short term; his primary talent is in staying afloat when the water is really, really cold.

I don’t mean to make these characters sound interchangeable. Leggy is slicker; Eddy is more romantic; Pete is more disciplined; Lyle is more centered. But they all share a certain innate Sterling-like cheerfulness.

Besides these linked stories, the collection contains other futures, some of them in the future, some of them not. Sterling is so often characterized as a futurist, it’s easy to forget that his range extends backwards as well as forwards, that he’s as interested in the futures of the past as he is in those of the future. (Who could trust a futurist who wasn’t?)

“Dinner in Audoghast” takes place in Northern Africa around the year 1040. In it, an opulent evening’s entertainment is marred by a leprous doom-prophesizing beggar. Part Cassandra, part Ozymandias, the story is the pure distillation of one of Sterling’s recurring themes. What does “Dinner in Audoghast” have in common with “The Blemmye’s Stratagem” (11th century, Holy Land), “Telliamed” (Marseille, 1737), “Flowers of Edo” (Kabukiza District, Edo, mid 1800s), “Our Neural Chernobyl” (Earth, 2056), “Swarm,” (2248, planetoid circling Betelgeuse), “Spider Rose” (2283, habitat orbiting Uranus), “Cicada Queen” (2354, suburbs of the Czarina-Kluster), and “Sunken Gardens” (2554, Mars)?

In all these stories, the future is descending like a foot on an anthill. There can only be one Lobster King. If you think you’re that guy, then maybe your happy ending is only one exoskeleton away. I’m guessing you’re not.

Three of the stories here—“The Little Magic Shop,” “The Sword of Damocles,” and “Dori Bangs”—are metafictional and experimental. “Dori Bangs” is noteworthy for being openly heartfelt—not a move Sterling makes often—and for ending in poetry. Sterling’s neither a writer who depends much on the white space in a story nor one who lingers at a resonant image. His style is and always has been exuberant, abundant, a combination of speed, noise, action, and, most of all, the dizzying accumulation of detail.

But take a look at the last paragraphs of the last story, “The Blemmye’s Stratagem.” It seems to me that what we have there is a poetic pause. Knowing how much Sterling admires the hearty, artless, genre stuff, I can only assume that any shift toward the literary is temporary and has come upon him by accident. Probably it would be rude to notice. So I’ve said nothing of the sort. You mistook me.

What Sterling tends to be admired most for is the level of invention in his work. Inventions that for other writers would underpin whole stories are crammed in here end over end. They often have nothing to do with the plot, but they have everything to do with the impact. More than the characters, more than the events, these tossed off inventions often feel like the point, the purpose of the story. One reads with the growing suspicion that maybe Sterling lives rather closer to the future than the rest of us do.

That’s a good l

ine, isn’t it? It’s not mine.

And the faster the future comes at us, the better Sterling’s mood seems to get. So these stories are not only fun to read, but also, taken as a group, oddly comforting. If Sterling sees what’s coming more clearly than I do, and he’s not upset by it, at least not until 2248 or thereabouts, why should I be?

Admittedly, Sterling’s comfort is the cold sort. In order to enjoy it, we have to avert our eyes from some troubling parallels between events on the ground in the far future story “Swarm” and the near future story “Taklamakan.” We have to stop minding so much about the terrorists and such like. But, and speaking just for me here, I wouldn’t believe in anything much warmer. Even from the pen of a world renowned, often quoted, much admired futurist like Bruce Sterling.

Foreword

by Bruce Sterling

Ascendancies is a compilation of my science fiction stories over the past three decades. This book is a career summary of sorts, so I feel a certain need to pull the fireproof curtain, bring you back into the hot, grimy forge here, and explain how these works came about.

I started reading science fiction stories at the age of thirteen. Before that time, I liked to read encyclopedias. In those pre-electronic days, encyclopedias were the densest textual knowledge I could find. There was something very refreshing to me in the way encyclopedias baldly tackled every conceivable issue wholesale. I thrived on that approach. Still, I didn’t write any encyclopedias. I tried to write stories.

My earliest, faltering stories, written as a young teen, concerned two simple topics, (1) everything that ever now or formerly existed and (2) anything I saw fit to make up. In a word, they were encyclopedic. My work hasn’t changed all that much since those days. I started as a young omnivore, I worked my way up to dilettante, and if I live long enough, I’ll be a polymath.

Eventually, I became a science fiction writer, mostly through the kindly efforts of other people. A lot of authors loudly moan that writing is a lonely, neglected profession, but I never lacked for help and succor. Loved ones were positive, mentors and colleagues were thoughtful and honest, the fan community was supportive. I wrote almost all these stories in Austin, a particularly readerly city. You wouldn’t guess it from the dire, edgy, hard-scrabble tone of some of these texts, but life was sweet.

As an oil-company émigré kid much given to globetrotting, I quite liked it that there were aliens in science fiction. It particularly pleased me that so many of those aliens were the writers. Not just a host of deeply alienated American writers, whom I idolized. There were people like Stanislaw Lem: a Polish Communist was probably the best science fiction writer in the world. William Burroughs. Burroughs was a queer beatnik junkie. He was canaille. You couldn’t even mention his name to teachers, to parents. Jules Verne, that hundred-year-old French Bohemian. And Italo Calvino. Calvino was doing things with ink on paper like nobody else on Earth. Calvino clearly had some kind of distinct agenda; you could really smell the midnight oil burning there. “Cosmicomics” Whatever that was, that Italian guy was doing it on purpose.

I deeply admired practically every form of science fiction, especially the kinds that weren’t entertaining. I had a lasting professional interest in kinds of science fiction that people could barely endure reading. Victorian technothrillers. Outdated space operas. Soviet SF. Ticked-off feminist SF tracts: I took particular interest in those because it was so clear that I wasn’t supposed to understand them.

I was always impressed by science fiction’s deeply oxymoronic aspects: that it was wondrous yet trashy, elite yet cheap, obscure yet global, cosmic yet a gutter literature, a literature-of-ideas scared by literary ideologies. You may notice that all these contradictions are also true of the Internet now.

In my youth, science fiction writers were supposed to be hands-on paperback midlist guys who could dent the wire racks with truckloads of popular product. I was totally into that business model, but I turned out to be a rather artsy, fussy, highbrow, theory-driven, critics’-darling kind of science fiction writer. As you can see by these stories, I tried hard to avoid that. My basic attitude to the enterprise was about as determinedly pulpy and street-level as they come, but after thirty years of writing science fiction, I nevertheless became what I am. At this point in my life, I’m some kinda gypsy-scholar cyberpunk aesthete who writes for glossy magazines, teaches in design schools and keynotes European tech conferences. I have to admit I’m a little crestfallen.

Given a book like this one, though, the evidence is just irrefutable. I wonder guiltily what my spiritual ancestors would think of me.

Take, for instance, Robert E. Howard, who is definitely the patron saint of Texan science fiction writers like myself. “Two-Gun Bob,” they used to call him. Howard was a raging, off-kilter guy from a scarily isolated West Texas village who, in order to save money and paper during the depths of the Depression, would type a new story between the lines of an earlier manuscript. God knows what he did for ribbon ink. Or H.P. Lovecraft: living on 19 cents a day while writing endless morale-boosting letters to the far-flung members of his literary coterie. I’ve got a literary coterie, too, but at least I can send them email. I still bite my lips about Henry Kuttner. Kuttner could appear in ten or twelve SF magazines all at once, writing under a dozen pseudonyms, writing a new story every day. I once wrote a story in a single day, just like Henry Kuttner. Yeah, I did that: once.

Howard shot himself, Lovecraft perished of malnutrition and Kuttner died of a heart attack from too much desk work, but the Gothic prospect of writerly immolation never deterred me. Not a bit of it. Us 1970s rock ’n’ roll counterculture no-future punk types, we considered that sort of activity romantic. Nevertheless, I have conspicuously failed to drop dead. As far as I can tell, I’m not even close. On the contrary, now that I’m in my supposedly stolid and sensible ’50s, years when I ought to be finding a favorite easy chair, my life has become wildly frenetic: I travel incessantly and I scribble reams of scattershot journalism about design, architecture, politics, science.… I’ve already lived twice as long as John Keats.

As this tome amply demonstrates, my pen has gleaned my teeming brain in a high-piled book like a rich garner of the full-ripened grain (as young Mr. Keats used to put it). What might Mr. Keats make of the goods purveyed here? His poesy rarely lacked for the florid and phantastic, but I mean, really: spacey posthumans, intelligent raccoons, anarchist bike mechanics… stand-up comedians from Meiji Japan, computer-crime investigators… Furthermore, Ascendancies contains the calmer, more lucid and considered material from the Sterling oeuvre.

Keats was a gifted critic and had things to say about writing that I took to heart: yes, “load every rift with ore.” I have ored my share of rifts in here, but would Keats be able to parse a single paragraph? I might mention that John Keats himself appears as a minor character in one of my novels. Not as a poet. He’s a computer programmer. That may have been impolite of me.

There’s just no getting around it: these stories are plenty weird. They’re not merely about weird topics. These texts are conjured up and stuck together in peculiar, idiosyncratic ways. Since I’ve been known to write reviews, I know what stories are supposed to look like. These stories don’t look much like that. My stories strongly tend to be laborious and overcrowded, with frazzled wiring and excessive moving parts. They writhe in organic profusion. They’re antic, snarled and open-ended. This book makes it pretty obvious that I’ve worked like that during my entire creative life. Somehow, I must know what I’m doing.

It alarms me now to see how much these texts, many of them written on typewriters decades ago, look and feel like contemporary websurfing. They have that cyberized “more is more” aesthetic, like techno music and software art. Sometimes it’s pitifully easy to predict the future.

As a weblogger and tech journalist, I find myself doing a great deal of web-surfing these days. I work on computer screens much more than I work on paper. Websurfing is ominously different from classical literatu

re, in that it’s machine-assisted and basically infinite in scope. Websurfing bears the relationship to reading that movies do to oil-paint. Email, web-posts, digital photographs, streaming speeches on video.… The web has no ends, no beginnings, no arc of development, no denouement, no plot. The web has no center, no heart. The web has data. It has tags and terms. Increasingly, the web has something like a native semantics. As a tech journalist and futurist, I’m fascinated; as a literateur, I look on these developments with alarmed misgivings. They’re just not well understood. I ought to be in the business of understanding a transition like that. Frankly, I can’t say that I do.

It worries me that the Internet suits my own sensibilities so much better than ink on paper ever did. These stories of mine are still “stories,” but instead of being well-contained verbal contrivances, disciplined and redolent of literary-cultural sensemaking, Sterling texts generally look-and-feel like they could do with some hotlinks and keywords. Maybe a scrollbar.

Sterling stories are nets of ideas and images that have been bent, tucked and pruned into a pocket world. Their literary sensibility—and they do have one—is in the worldbuilding. It’s about the settings, the semiotics. And the feelings. Not the characters’ feelings—mostly, the key to these stories is the narrator’s feelings. With one brisk exception, the narrator’s not a character within these stories, but he’s the busiest guy in this book. In his lighter moments, he exhibits a certain amiable boyish gusto, like some kid happily mangling encyclopedias. His most common affect, as he razors and duct-tapes, is sinister glee.

The writer of these pieces, like a lot of comedians, has a rather dark muse. His inner child is the kind of kid that pokes anthills with a stick. The lad just can’t let those ants be; he direly needs to satirize the ants a little, to jolt them out of their mental ant-box. Science fiction writing can be a problematic effort. Annoying ants is not a major literary enterprise. Why? Because ants don’t get illuminated by that artistic intervention; ants are just ants. Imagined worlds have so many phony, sandbox aspects.… science fiction makes head-fakes toward profundity, which too often turn out to be mere sleights of hand, in-jokes, trivial paradoxes, vaudeville.… Like a trained flea-circus, where the fleas are dressed as six-armed Martian swordsmen.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

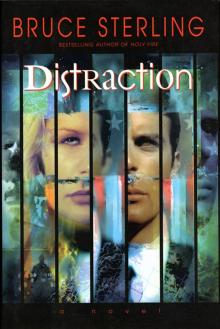

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase