- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Ascendancies Page 2

Ascendancies Read online

Page 2

Sense of wonder? Too short a shelf-life. Blowing people’s minds? Like stage magic, that’s done mostly through misdirection. Happy, upbeat endings? Depends on when you stop telling the story.

Are there other burning lamentations one might offer about the cruel creative agony and the dire existential limits involved in writing science fiction stories? Well, now that you insist on asking me, yeah. For instance, this big Bruce Sterling collection sure does have a lot of Bruce Sterling in it. My other story collections tend to feature some pleasant collaborations with other writers, which break up that relentless Sterlingness.

I used to spend rather a lot of my time and energy trying to write stories that nobody else could write. You know: unique, original, ground-breaking, non-derivative work. Young writers suffer anxiety-of-influence, so they attempt a lot of that. Some of these stories are much in that vein. “Finding one’s own voice,” they call that.

It might also be dignified with the term “self-actualization.” Self-actualization is a conceptual, very writerly game in which one tries to become as much like Bruce Sterling as one can. There’s much to be said for that activity, especially if one actually is Bruce Sterling. However, when a science fiction writer pursues that line of development, in that particularly oracular and eccentric science-fictional way, it can be rather trying to the reader. “Okay, fine, pal, nobody but you could have ever conceived of that notion. That was totally, utterly unheard-of. Great. So how come I have to read about that?” Now that you ask, that’s another good question.

The way that certain SF writers cough up those raw crunchy nuggets of the barely thinkable… well, that’s one of the connoisseur delights of SF as a genre. It’s like whales and their ambergris. Rare and superb in small amounts, rather scary in large beached lumps. Furthermore, as an artistic program, it’s dubious. Suppose you’re radically self-actualized, but you’re also a delusional goofball. Wouldn’t you do better by seeking some cues from objective reality, rather than hearkening always to those magic promptings of the inner self?

Furthermore: just suppose that, like me, your inner self is, for obscure design-fan reasons, deeply inspired by forks, manhole covers and doorknobs, rather than raucous, technicolor, crowd-pleasing sci-fi gizmos such as robots, rocketships and time machines. If you write a sci-fi book about forks and manhole covers, will that be a great work? No. It won’t. Because forks and manhole covers are not entertaining. They’re boring. Not to you, of course; you adore manhole covers. Manhole covers are very you. But they’re also incredibly boring. They just plain are.

Original genius, that’s not everything in the world. The world is more significant than the inside of anybody’s head. Sometimes you’re well-advised to just get over yourself.

If your thoughts were genuinely original—literally unthinkable by other people—then you could never express them in a language sharable with readers. That’s not what writing is about. Literature is a heritage. Language is a commons. Language is centuries old and enriched by thousands of minds. Language and literature need to be treated with a sensitivity and care which doesn’t always mesh with raw, kraken-busting sci-fi aesthetics. I know that, and I further know that, as a writer, I ought to do better at that. Is there any clear sign of my making any progress along that front, within these stories? Am I fighting the good fight here, or am I pretty much part of the problem? I do have to wonder.

A writer pestered with truly original thoughts would have to make up new nouns, new verbs. Frankly, I do a great deal of that. My writing in this book—in all my books—is cram-full of invented jargon and singular idiolects. It’s a signature riff of mine that I compose a great many words and terms that no mere computer spell-checker understands. I’m trying to get a little subtler about that. It works best when people don’t notice I’m doing it.

With all this anguished authorly handwringing, you might wonder how stories like these get written at all. But they do get written; they even get finished and sent off to publishers. I got one coming out next month. It’s not in this book, but man, it’s aces. I’ve got a hundred ideas for other ones—really weird ideas—but, well, ideas aren’t stories. As stories, I’ve yet to get them done.

A Sterling story is generally done—or it stops, at least—when the writer’s inner creative daemon has fully stacked up its Lego blocks.

Rational analysis is never the strong suit of the inner daemon. The inner daemon is profoundly creative, yet he’s rather stupid. A creative daemon by nature is a rather simple, headstrong being who sees the cosmos as daemon-friendly toy-blocks. The daemon assembles a mental world from a raw confusion into some meaningful coherency. He does that through assembling his blocks. The daemon himself is made of the blocks. He’s not a conscious personality, he’s much lower in the chain-of-being than that; the daemon is a sense-making network, some pre-conscious society-of-mind. The daemon is a capturer of imagination. That’s his reason for being.

When the daemon is on top of his game, he can whip up a story from his shadowy basement of mentality. A story is a tower of blocks, one with some coherent structure of feeling. A story says something evocative about the world, it somehow means something… Then the conscious mind can bind that in wire, slap on a label and ship it.

That’s how I write stories. That’s how these works came into being. Thanks for putting up with that confession. I rather hope to do a lot more of that. I don’t do it with any particular regularity because I’m not fully in control of the process. The same goes for a lot of artists. You learn to live with that.

So: a few closing notes now somehow seem necessary. Let me explain the title of this book. From some mysterious cataloging bug or cyber-mechanical oversight, a book called “Ascendancies” was attributed to me back in 1987. “Ascendancies” frequently appears in bibliographies of mine. For years, people have written me eager fan mail determined to locate my book, “Ascendancies”. I never wrote that book. I don’t think I ever used the word, either. Still “Ascendancies” is quite a pretty-looking word, almost a palindrome: “Seicnadnecsa.” It’ll do.

Better yet, the sudden appearance of a genuine “Ascendancies” by Bruce Sterling, a full twenty years in the future after its announced publication date, is a time-travel paradox that will drive bibliographers nuts. Deeply confusing my audience, librarians, and the industry in toto: hey, just another service we offer.

In conclusion, I’d like to formally thank every rugged, determined, anonymous consumer who, through a host of small purchases, has given American science fiction something like an economic basis. Nobody ever thanks these noble people; they’re considered to be some kind of vast, rumbling mass audience, but, well, they’re all individuals. Every one of them is individual. Reading is a solitary pursuit. Writing as an art is the mingling of one mind with one other. But there are lots of American readers, and thank goodness. In some smaller society with a smaller language, I’d have quite likely done this sort of thing anyway, yet never been paid one shekel, ruble, peso, real or dinar. So that was great luck for all concerned, eh? Fate has truly been kind! Let’s hope we all do more of that!

PART I:

THE SHAPER/MECHANIST STORIES

Swarm

“I will miss your conversation during the rest of the voyage,” the alien said.

Captain-Doctor Simon Afriel folded his jeweled hands over his gold-embroidered waistcoat. “I regret it also, ensign,” he said in the alien’s own hissing language. “Our talks together have been very useful to me. I would have paid to learn so much, but you gave it freely.”

“But that was only information,” the alien said. He shrouded his bead-bright eyes behind thick nictitating membranes. “We Investors deal in energy, and precious metals. To prize and pursue mere knowledge is an immature racial trait.” The alien lifted the long ribbed frill behind his pinhole-sized ears.

“No doubt you are right,” Afriel said, despising him. “We humans are as children to other races, however; so a certain immaturity seems natura

l to us.” Afriel pulled off his sunglasses to rub the bridge of his nose. The star-ship cabin was drenched in searing blue light, heavily ultraviolet. It was the light the Investors preferred, and they were not about to change it for one human passenger.

“You have not done badly,” the alien said magnanimously. “You are the kind of race we like to do business with: young, eager, plastic, ready for a wide variety of goods and experiences. We would have contacted you much earlier, but your technology was still too feeble to afford us a profit.”

“Things are different now,” Afriel said. “We’ll make you rich.”

“Indeed,” the Investor said. The frill behind his scaly head flickered rapidly, a sign of amusement. “Within two hundred years you will be wealthy enough to buy from us the secret of our starflight. Or perhaps your Mechanist faction will discover the secret through research.”

Afriel was annoyed. As a member of the Reshaped faction, he did not appreciate the reference to the rival Mechanists. “Don’t put too much stock in mere technical expertise,” he said. “Consider the aptitude for languages we Shapers have. It makes our faction a much better trading partner. To a Mechanist, all Investors look alike.”

The alien hesitated. Afriel smiled. He had appealed to the alien’s personal ambition with his last statement, and the hint had been taken. That was where the Mechanists always erred. They tried to treat all Investors consistently, using the same programmed routines each time. They lacked imagination.

Something would have to be done about the Mechanists, Afriel thought. Something more permanent than the small but deadly confrontations between isolated ships in the Asteroid Belt and the ice-rich Rings of Saturn. Both factions maneuvered constantly, looking for a decisive stroke, bribing away each other’s best talent, practicing ambush, assassination, and industrial espionage.

Captain-Doctor Simon Afriel was a past master of these pursuits. That was why the Reshaped faction had paid the millions of kilowatts necessary to buy his passage. Afriel held doctorates in biochemistry and alien linguistics, and a master’s degree in magnetic weapons engineering. He was thirty-eight years old and had been Reshaped according to the state of the art at the time of his conception. His hormonal balance had been altered slightly to compensate for long periods spent in free-fall. He had no appendix. The structure of his heart had been redesigned for greater efficiency, and his large intestine had been altered to produce the vitamins normally made by intestinal bacteria. Genetic engineering and rigorous training in childhood had given him an intelligence quotient of one hundred and eighty. He was not the brightest of the agents of the Ring Council, but he was one of the most mentally stable and the best trusted.

“It seems a shame,” the alien said, “that a human of your accomplishments should have to rot for two years in this miserable, profitless outpost.”

“The years won’t be wasted,” Afriel said.

“But why have you chosen to study the Swarm? They can teach you nothing, since they cannot speak. They have no wish to trade, having no tools or technology. They are the only spacefaring race that is essentially without intelligence.”

“That alone should make them worthy of study.”

“Do you seek to imitate them, then? You would make monsters of yourselves.” Again the ensign hesitated. “Perhaps you could do it. It would be bad for business, however.”

There came a fluting burst of alien music over the ship’s speakers, then a screeching fragment of Investor language. Most of it was too high-pitched for Afriel’s ears to follow.

The alien stood, his jeweled skirt brushing the tips of his clawed bird-like feet. “The Swarm’s symbiote has arrived,” he said.

“Thank you,” Afriel said. When the ensign opened the cabin door, Afriel could smell the Swarm’s representative; the creature’s warm yeasty scent had spread rapidly through the starship’s recycled air.

Afriel quickly checked his appearance in a pocket mirror. He touched powder to his face and straightened the round velvet hat on his shoulder-length reddish-blond hair. His earlobes glittered with red impact-rubies, thick as his thumbs’ ends, mined from the Asteroid Belt. His knee-length coat and waistcoat were of gold brocade; the shirt beneath was of dazzling fineness, woven with red-gold thread. He had dressed to impress the Investors, who expected and appreciated a prosperous look from their customers. How could he impress this new alien? Smell, perhaps. He freshened his perfume.

Beside the starship’s secondary airlock, the Swarm’s symbiote was chittering rapidly at the ship’s commander. The commander was an old and sleepy Investor, twice the size of most of her crewmen. Her massive head was encrusted in a jeweled helmet. From within the helmet her clouded eyes glittered like cameras.

The symbiote lifted on its six posterior legs and gestured feebly with its four clawed forelimbs. The ship’s artificial gravity, a third again as strong as Earth’s, seemed to bother it. Its rudimentary eyes, dangling on stalks, were shut tight against the glare. It must be used to darkness, Afriel thought.

The commander answered the creature in its own language. Afriel grimaced, for he had hoped that the creature spoke Investor. Now he would have to learn another language, a language designed for a being without a tongue.

After another brief interchange the commander turned to Afriel. “The symbiote is not pleased with your arrival,” she told Afriel in the Investor language. “There has apparently been some disturbance here involving humans, in the recent past. However, I have prevailed upon it to admit you to the Nest. The episode has been recorded. Payment for my diplomatic services will be arranged with your faction when I return to your native star system.”

“I thank Your Authority,” Afriel said. “Please convey to the symbiote my best personal wishes, and the harmlessness and humility of my intentions…” He broke off short as the symbiote lunged toward him, biting him savagely in the calf of his left leg. Afriel jerked free and leapt backward in the heavy artificial gravity, going into a defensive position. The symbiote had ripped away a long shred of his pants leg; it now crouched quietly, eating it.

“It will convey your scent and composition to its nestmates,” said the commander. “This is necessary. Otherwise you would be classed as an invader, and the Swarm’s warrior caste would kill you at once.”

Afriel relaxed quickly and pressed his hand against the puncture wound to stop the bleeding. He hoped that none of the Investors had noticed his reflexive action. It would not mesh well with his story of being a harmless researcher.

“We will reopen the airlock soon,” the commander said phlegmatically, leaning back on her thick reptilian tail. The symbiote continued to munch the shred of cloth. Afriel studied the creature’s neckless segmented head. It had a mouth and nostrils; it had bulbous atrophied eyes on stalks; there were hinged slats that might be radio receivers, and two parallel ridges of clumped wriggling antennae, sprouting among three chitinous plates. Their function was unknown to him.

The airlock door opened. A rush of dense, smoky aroma entered the departure cabin. It seemed to bother the half-dozen Investors, who left rapidly. “We will return in six hundred and twelve of your days, as by our agreement,” the commander said.

“I thank Your Authority,” Afriel said.

“Good luck,” the commander said in English. Afriel smiled.

The symbiote, with a sinuous wriggle of its segmented body, crept into the airlock. Afriel followed it. The airlock door shut behind them. The creature said nothing to him but continued munching loudly. The second door opened, and the symbiote sprang through it, into a wide, round stone tunnel. It disappeared at once into the gloom.

Afriel put his sunglasses into a pocket of his jacket and pulled out a pair of infrared goggles. He strapped them to his head and stepped out of the airlock. The artificial gravity vanished, replaced by the almost imperceptible gravity of the Swarm’s asteroid nest. Afriel smiled, comfortable for the first time in weeks. Most of his adult life had been spent in free-fall, in the Shapers’

colonies in the Rings of Saturn.

Squatting in a dark cavity in the side of the tunnel was a disk-headed furred animal the size of an elephant. It was clearly visible in the infrared of its own body heat. Afriel could hear it breathing. It waited patiently until Afriel had launched himself past it, deeper into the tunnel. Then it took its place in the end of the tunnel, puffing itself up with air until its swollen head securely plugged the exit into space. Its multiple legs sank firmly into sockets in the walls.

The Investors’ ship had left. Afriel remained here, inside one of the millions of planetoids that circled the giant star Betelgeuse in a girdling ring with almost five times the mass of Jupiter. As a source of potential wealth it dwarfed the entire solar system, and it belonged, more or less, to the Swarm. At least, no other race had challenged them for it within the memory of the Investors.

Afriel peered up the corridor. It seemed deserted, and without other bodies to cast infrared heat, he could not see very far. Kicking against the wall, he floated hesitantly down the corridor.

He heard a human voice. “Dr. Afriel!”

“Dr. Mirny!” he called out. “This way!”

He first saw a pair of young symbiotes scuttling toward him, the tips of their clawed feet barely touching the walls. Behind them came a woman wearing goggles like his own. She was young, and attractive in the trim, anonymous way of the genetically reshaped.

She screeched something at the symbiotes in their own language, and they halted, waiting. She coasted forward, and Afriel caught her arm, expertly stopping their momentum.

“You didn’t bring any luggage?” she said anxiously.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

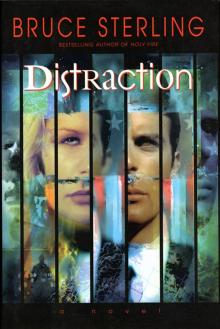

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase