- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Globalhead Page 2

Globalhead Read online

Page 2

There remains, however, the previously unsuspected connection between advanced dendritic branching and manual dexterity, which Dr. Hotton tackles in his sixth chapter. This concept has caused a revolution in paleoanthropology. We are now forced into the uncomfortable realization that Pithecanthropus robustus, formerly dismissed as a large-jawed, vegetable-chewing ape, was probably far more intelligent than Homo sapiens. CAT-scans of the recently discovered Tanzanian fossil skeleton, nicknamed “Leonardo,” reveal a Pithecanthropus skull-ridge obviously rich with dendritic branching. It has been suggested that the pithecanthropoids suffered from a heightened “life of the mind” similar to the life-threatening, absent-minded genius of terminal neural chernobyl sufferers. This yields the uncomfortable theory that nature, through evolution, has imposed a “primate stupidity barrier” that allows humans, unlike Pithecanthropus, to get on successfully with the dumb animal business of living and reproducing.

But the synergetic effects of dendritic branching and manual dexterity are clear in a certain nonprimate species. I refer, of course, to the well-known “chernobyl jump” of Procyon lotor, the American raccoon. The astonishing advances of the raccoon, and its Chinese cousin the panda, occupy the entirety of Chapter 8.

Here Dr. Hotton takes the so-called “modern view,” from which I must dissociate myself. I, for one, find it intolerable that large sections of the American wilderness should be made into “no-go areas” by the vandalistic activities of our so-called “stripe-tailed cousins.” Admittedly, excesses may have been committed in early attempts to exterminate the verminous, booming population of these masked bandits. But the damage to agriculture has been severe, and the history of kamikaze attacks by self-infected rabid raccoons is a terrifying one.

Dr. Hotton holds that we must now “share the planet with a fellow civilized species.” He bolsters his argument with hearsay evidence of “raccoon culture” that to me seems rather flimsy. The woven strips of bark known as “raccoon wampum” are impressive examples of animal dexterity, but to my mind it remains to be proven that they are actually “money.” And their so-called “pictographs” seem little more than random daubings. The fact remains that the raccoon population continues to rise exponentially, with raccoon bitches whelping massive litters every spring. Dr. Hotton, in a footnote, suggests that we can relieve crowding pressure by increasing the human presence in outer space. This seems a farfetched and unsatisfactory scheme.

The last chapter is speculative in tone. The prospect of intelligent rats is grossly repugnant; so far, thank God, the tough immune system of the rat, inured to bacteria and filth, has rejected retroviral invasion. Indeed, the feral cat population seems to be driving these vermin toward extinction. Nor have opossums succumbed; indeed, marsupials of all kinds seem immune, making Australia a haven of a now-lost natural world. Whales and dolphins are endangered species; they seem unlikely to make a comeback even with the (as-yet-unknown) cetacean effects of chernobyling. And monkeys, which might pose a very considerable threat, are restricted to the few remaining patches of tropical forest and, like humans, seem resistant to the disease.

Our neural chernobyl has bred a folklore all its own. Modern urban folklore speaks of “ascended masters,” a group of chernobyl victims able to survive the virus. Supposedly, they “pass for human,” forming a hidden counterculture among the normals, or “sheep.” This is a throwback to the dark tradition of Luddism, and the popular fears once projected onto the dangerous and reckless “priesthood of science” are now transferred to these fairy tales of supermen. This psychological transference becomes clear when one hears that these “ascended masters” specialize in advanced scientific research of a kind now frowned upon. The notion that some fraction of the population has achieved physical immortality, and hidden it from the rest of us, is utterly absurd.

Dr. Hotton, quite rightly, treats this paranoid myth with the contempt it deserves.

Despite my occasional reservations, this is a splendid book, likely to be the definitive work on this central phenomenon of modern times. Dr. Hotton may well hope to add another Pulitzer to his list of honors. At ninety-five, this grand old man of modern science has produced yet another stellar work in his rapidly increasing oeuvre. His many readers, like myself, can only marvel at his vigor and clamor for more.

—for Greg Bear

STORMING

THE COSMOS

By RUDY RUCKER AND BRUCE STERLING

I first met Vlad Zipkin at a Moscow beatnik party in the glorious winter of 1957. I went there as a KGB informer. Because of my report on that first meeting, poor Vlad had to spend six months in a mental hospital—not that he wasn’t crazy.

As a boy I often tattled on wrongdoers, but I certainly didn’t plan to grow up to be a professional informer. It just worked out that way. The turning point was the spring of 1953, when I failed my completion exams at the All-Union Metallurgical Institute. I’d been working toward those exams for years; I wanted to help build the rockets that would launch us into the Infinite.

And then, suddenly, one day in April, it was all over. Our examination grades were posted, and I was one of the three in seventeen who’d failed. To take the exam again, I’d have to wait a whole year. First I was depressed, then angry. I knew for a fact that four of the students with good grades had cheated. I, who was honest, had failed; and they, who had cheated, had passed. It wasn’t fair, it wasn’t communist—I went and told the head of the Institute.

The upshot was that I passed after all, and became an assistant metallurgical engineer at the Kaliningrad space center. But, in reality, my main duty was to make weekly reports to the KGB on what my co-workers thought and said and did. I was, frankly, grateful to have my KGB work to do, as most of the metallurgical work was a bit beyond me.

There is an ugly Russian word for informer: stukach, snitch. The criminals, the psychotics, the parasites, and the beatniks—to them I was a stukach. But without stukachi, our communist society would explode into anarchy or grind to a decadent halt. Vlad Zipkin might be a genius, and I might be a stukach—but society needed us both.

I first met Vlad at a party thrown by a girl called Lyuda. Lyuda had her own Moscow apartment; her father was a Red Army colonel-general in Kaliningrad. She was a nice, sexy girl who looked a little like Doris Day.

Lyuda and her friends were all beatniks. They drank a lot, they used English slang, they listened to jazz; and the men hung around with prostitutes. One of the guys got Lyuda pregnant and she went for an abortion. She had VD as well. We heard of this, of course. Word spreads about these matters. Someone in Higher Circles decided to eliminate the anti-social sex gangster responsible for this. It was my job to find out who he was.

It was a matter for space-center KGB because several rocket-scientists were known to be in Lyuda’s orbit. My approach was cagey. I made contact with a prostitute called Trina who hung around the Metropol, the Moskva, and other foreign hotels. Trina had chic Western clothes from her customers, and she was friends with many of the Moscow beatniks. I’m certainly not dashing enough to charm a girl like Trina—instead, I simply told her that I was KGB, and that if she didn’t get me into one of Lyuda’s bashes I’d have her arrested.

Lyuda’s pad was jammed when we got there. I was proud to show up with a cool chick like Trina on my arm. I looked very sharp, too, with the leather jacket, and the black stove-pipe pants with no cuffs that all the beatniks were wearing that season. Trina stuck right with me—as we’d planned—and lots of men came up to talk to us. Trina would get them to talking dirty, and then I’d make some remark about Lyuda, ending with “but I guess she has a boyfriend?” The problem was that she had lots of them. I kept having to sneak into the bathroom to write down more names. Somehow I had to decide on one particular guy.

Time went on, and I got tenser. Cigarette smoke filled the room. The bathroom was jammed and I had to wait. When I came back I saw Trina with a hardcore beatnik named Starsky—he got her attention with some garbled Americanisms

: “Hey baby, let’s jive down to Hollywood and drink cool Scotch. I love making it with gone broads like you and Lyuda.” He showed her a wad of hard currency—dollars he had illegally bought from tourists. I decided on the spot that Starsky was my man, and told Trina to leave with him and find out where he lived.

Now that I’d finished my investigation, I could relax and enjoy myself. I got a bottle of vodka and sat down by Lyuda’s Steinway piano. Some guy in sunglasses was playing a slow boogie-woogie. It was lovely, lovely enough to move me to tears—tears for Lyuda’s corrupted beauty, tears for my lost childhood, tears for my mother’s grave.

A sharp poke in the thigh interrupted my reverie.

“Quit bawling, fatso, this isn’t the Ukraine.”

The voice came from beneath the piano. Leaning down, I saw a man sitting cross-legged there, a thin, blond man with pale eyes. He smiled and showed his bad teeth. “Cheer up, pal, I mean it. And pass me that vodka bottle you’re sucking. My name’s Vlad Zipkin.”

I passed him my bottle. “I’m Nikita Iosifovich Globov.”

“Nice shoes,” Vlad said admiringly. “Cool jacket, too. You’re a snappy dresser, for a rocket-type.”

“What makes you think I’m from the space center?” I said.

Vlad lowered his voice. “The shoes. You got those from Nokidze the Kazakh, the black-market guy. He’s been selling ’em all over Kaliningrad.”

I climbed under the piano with Zipkin. The air was a little clearer down there. “You’re one of us, Comrade Zipkin?”

“I do information theory,” Zipkin whispered, drunkenly touching one finger to his lips. “We’re designing error-proof codes for communicating with the … you know.” He made a little orbiting movement with his forefinger and looked upward at the shiny dark bottom of the piano. The Sputnik had only been up since October. We space workers were still not used to talking about it in public.

“Come on, don’t be shy,” I said, smiling. “We can say ‘Sputnik,’ can’t we? Everyone in the world has talked of nothing else for months!”

It was easy to draw Vlad out. “My group’s hush-hush,” he bragged criminally. “The top brass think ‘information theory’ has to be classified and censored. But the theory’s not information itself, it’s an abstract meta-information …” He burbled on a while in the weird jargon of his profession. I grew bored and opened a pack of Kent cigarettes.

Vlad bummed one instantly. He was impressed that I had American cigarettes. Only cool black-market operators had classy cigs like that. Vlad felt the need to impress me in return. “Khrushchev wants the next sputnik to broadcast propaganda,” he confided, blowing smoke. “The Internationale in outer space—what foolishness!” Vlad shook his head. “As if countries matter any more outside our atmosphere. To any real Russian, it is already clear that we have surpassed the Americans. Why should we copy their fascist nationalism? We have soared into the void and left them in the dirt!” He grinned. “Damn, these are good smokes. Can you get me a connection?”

“What are you offering?” I said.

He nodded at Lyuda. “See our hostess? See those earrings she has? They’re gold-plated transistors I stole from the Center! All property is theft, hey Nikita?”

I liked Vlad well enough, but I felt duty-bound to report his questionable attitudes along with my information about Starsky. Political deviance such as Vlad’s is a type of mental illness. I liked Vlad enough to truly want to see him get better.

Having made my report, I returned to Kaliningrad, and forgot about Vlad. I didn’t hear about him for a month.

Since the early ’50s, Kaliningrad had been the home of the Soviet space effort. Kaliningrad was thirty kilometers north of Moscow and had once been a summer resort. There we worked heroically at rocket research and construction—though the actual launches took place at the famous Baikonur Cosmodrome, far to the south. I enjoyed life in Kaliningrad. The stores were crammed with Polish hams and fresh lamb chops, and the landscape of forests and lakes was romantic and pleasant. Security was excellent.

Outside the research complex and block apartments were dachas, resort homes for space scientists, engineers, and party officials, including our top boss, the Chief Designer himself. The entire compound was surrounded by a high wood-and-concrete fence manned around the clock by armed guards. It was very peaceful. The compound held almost fifty dachas. I owned a small one—a kitchen and two rooms—with a large garden filled with fruit trees and berry bushes, now covered by winter snow.

A month after Lyuda’s party, I was enjoying myself in my dacha, quietly pressing a new suit I had bought from Nokidze the Kazakh, when I heard a black ZIL sedan splash up through the mud outside. I peeked through the curtains. A woman stamped up the path and knocked. I opened the door slightly.

“Nikita Iosifovich Globov?”

“Yes?”

“Let me in, you fat sneak!” she said.

I gaped at her. She addressed me with filthy words. Shocked, I let her in. She was a dusky, strong-featured Tartar woman dressed in a cheap black two-piece suit from the Moscow G.U.M. store. No woman in Kaliningrad wore clothes or shoes that ugly, unless she was a real hard-liner. So I got worried. She kicked the door shut and glared at me.

“You turned in Vladimir Zipkin!”

“What?”

“Listen, you meddling idiot, I’m Captain Nina Bogulyubova from Information Mechanics. You’ve put my best worker into the mental hospital! What were you thinking? Do you realize what this will do to my production schedules?”

I was caught off guard. I babbled something about proper ideology coming first.

“You louse!” she snarled. “It’s my department and I handle Security there! How dare you report one of my people without coming to me first? Do you see me turning in metallurgists?”

“Well, you can’t have him babbling state secrets to every beatnik in Moscow!” I said defensively.

“You forget yourself,” said Captain Bogulyubova with a taut smile. “I have a rank in KGB and you are a common stukach. I can make a great deal of trouble for you. A very great deal.”

I began to sweat. “I was doing my duty. No one can deny that. Besides, I didn’t know he was in the hospital! All he needed was a few counselling sessions!”

“You fouled up everything,” she said, staring at me through slitted eyes like a Cossack sizing up a captured hog. She crossed her arms over her hefty chest and looked around my dacha. “This little place of yours will be nice for Vlad. He’ll need some rest. Poor Vlad. No one else from my section will want to work with him after he gets out. They’ll be afraid to be seen with him! But we need him, and you’re going to help me. Vlad will work here, and you’ll keep an eye on him. It can be a kind of house arrest.”

“But what about my work in metallurgy?”

She glared at me. “Your new work will be Comrade Zipkin’s rehabilitation. You’ll volunteer to do it, and you’ll tell the Higher Circles that he’s become a splendid example of communist dedication! He’d better get the Order of Lenin, understand?”

“This isn’t fair, Comrade Captain. Be reasonable!”

“Listen, you hypocrite swine, I know all about you and your black-market dealings. Those shoes cost more than you make in a month!” She snatched the iron off the end of my board and slammed it flat against my brand new suit. Steam curled up.

“All right!” I cried, wringing my hands. “I’ll help him.” I yanked the suit away and splashed water on the scorched fabric.

Nina laughed and stormed out of the house. I felt terrible. A man can’t help it if he needs to dress well. It’s unfair to hold a thing like that over someone.

Months passed. The spring of 1958 arrived. The dog Laika had been shot into the cosmic void. A good dog, a Russian, an Earthling. The Americans’ first launches had failed, and then in February they shot up a laughable sputnik no bigger than a grapefruit. Meanwhile we metallurgists forged ahead on the mighty RD-108 Supercluster paraffin-fueled engine, which would lift our

first cosmonaut into the Infinite. There were technical snags, and gross lapses in space-worker ideology, but much progress was made.

Captain Nina dropped by several times to bluster and grumble about Vlad. She blamed me for everything, but it was Vlad’s problem. All one has to do, really, is tell the mental health workers what they want to hear. But Zipkin couldn’t seem to master this.

A third sputnik was launched in May 1958, with much instrumentation on board. Yet it failed to broadcast a coherent propaganda statement, much less sing the Internationale. Vlad was missed, and missed badly. I awaited Vlad’s return with some trepidation. Would he resent me? Fear me? Despise me?

For my part, I simply wanted Vlad to like me. In going over his dossier I had come to see that, despite his eccentricities, the man was indeed a genius. I resolved to take care of Vlad Zipkin, to protect him from his irrational sociopathic impulses.

A KGB ambulance brought Vlad and his belongings to my dacha early one Sunday morning in July. He looked pale and disoriented. I greeted him with false heartiness.

“Greetings Vladimir Eduardovich! It’s an honor and a joy to have you share my dacha. Come in, come in. I have yogurt and fresh gooseberries. Let me help you carry all that stuff inside!”

“So it was you.” Vlad was silent while we carried his suitcase and three boxes of belongings into the dacha. When I urged him to eat with me, his face took on a desperate cast. “Please, Globov, leave me alone now. Those months in the hospital—you can’t imagine what it’s been like.”

“Vladimir, don’t worry, this dacha is your home, and I’m your friend.”

Vlad grimaced. “Just let me spend the day alone in your garden, and don’t tell the KGB I’m antisocial. I want to conform, I do want to fit in, but for God’s sake, not today.”

“Vlad, believe me, I want only the best for you. Go out and lie in the hammock; eat the berries, enjoy the sun.”

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

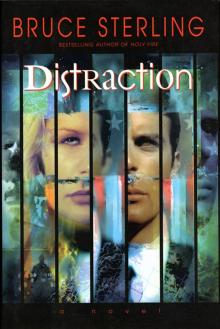

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase