- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Schismatrix Plus Page 4

Schismatrix Plus Read online

Page 4

“Then you’re blind to mankind’s whole cultural heritage.”

Ryumin looked surprised. “Strange talk for a Shaper. You’re an antiquarian, eh? Want to break the Interdict with Earth, study the so-called humanities, that sort of thing? That explains why you used the theatrical gambit. I had to use my lexicon to find out what a ‘play’ was. An astonishing custom. Are you really going through with it?”

“Yes. And the Black Medicals will finance it for me.”

“I see. The Geisha Bank won’t care for that. Loans and finance are their turf.”

Lindsay sat on the floor beside a nest of wires. He plucked the Black Medicals pin from his collar and twirled it in his fingers. “Tell me about them.”

“The Geishas are whores and financiers. You must have noticed that your credit card is registered in hours.”

“Yes.”

“Those are hours of sexual service. The Mechanists and Shapers use kilowatts as currency. But the System’s criminal element must have a black market to survive. A great many different black currencies have seen use. I did an article on it once.”

“Did you?”

“Yes. I’m a journalist by profession. I entertain the jaded among the System’s bourgeoisie with my startling exposés of criminality. Low-life antics of the sundog canaille.” He nodded at Lindsay’s bag. “Narcotics were the standard for a while, but that gave the Shaper black chemists an edge. Selling computer time had some success, but the Mechanists had the best cybernetics. Now sex has come into vogue.”

“You mean people come to this godforsaken place just for sex?”

“It’s not necessary to visit a bank to use it, Mr. Dze. The Geisha Bank has contacts throughout the cartels. Pirates dock here to exchange loot for portable black credit. We get political exiles from the other circumlunars, too. If they’re unlucky.”

Lindsay showed no reaction. He was one of those exiles.

His problem was simple now: survival. It was wonderful how this cleared his mind. He could forget his former life: the Preservationist rebellion, the political dramas he’d staged at the Museum. It was all history.

Let it fade, he thought. All gone now, all another world. He felt dizzy, suddenly, thinking about it. He’d lived. Not like Vera.

Constantine had tried to kill him with those altered insects. The quiet, subtle moths were a perfect modern weapon: they threatened only human flesh, not the world as a whole. But Lindsay’s uncle had taken Vera’s locket, booby-trapped with the pheromones that drove the deadly moths to frenzy. And his uncle had died in his place. Lindsay felt a slow, rising flush of nausea.

“And the exhausted come here from the Mechanist cartels,” Ryumin went on. “For death by ecstasy. For a price the Geisha Bank offers shinju: double suicide with a companion from the staff. Many customers, you see, take a deep comfort in not dying alone.”

For a long moment, Lindsay struggled with himself. Double suicide—the words pierced him. Vera’s face swam queasily before his eyes in the perfect focus of expanded memory. He pitched onto his side, retching, and vomited across the floor.

The drugs overwhelmed him. He hadn’t eaten since leaving the Republic. Acid scraped his throat and suddenly he was choking, fighting for air.

Ryumin was at his side in a moment. He dropped his bony kneecaps into Lindsay’s ribs, and air huffed explosively through his clogged windpipe. Lindsay rolled onto his back. He breathed in convulsively. A tingling warmth invaded his hands and feet. He breathed again and lost consciousness.

Ryumin took Lindsay’s wrist and stood for a moment, counting his pulse. Now that the younger man had collapsed, an odd, somnolent calm descended over the old Mechanist. He moved at his own tempo. Ryumin had been very old for a long time. The feeling changed things.

Ryumin’s bones were frail. Cautiously, he dragged Lindsay onto the tatami mat and covered him with a blanket. Then he stepped slowly to a barrel-sized ceramic water cistern, picked up a wad of coarse filter paper, and mopped up Lindsay’s vomit. His deliberate movements disguised the fact that, without video input, he was almost blind.

Ryumin donned his eyephones. He meditated on the tape he had made of Lindsay. Ideas and images came to him more easily through the wires.

He analyzed the young sundog’s movements frame by frame. The man had long, bony arms and shins, large hands and feet, but he lacked any awkwardness. Studied closely, his movements showed ominous fluidity, the sure sign of a nervous system subjected to subtle and prolonged alteration. Someone had devoted great care and expense to that counterfeit of footloose ease and grace.

Ryumin edited the tape with the reflexive ease of a century of practice. The System was wide, Ryumin thought. There was room in it for a thousand modes of life, a thousand hopeful monsters. He felt sadness at what had been done to the man, but no alarm or fear. Only time could tell the difference between aberration and advance. Ryumin no longer made judgments. When he could, he held out his hand.

Friendly gestures were risky, of course, but Ryumin could never resist the urge to make them and watch the result. Curiosity had made him a sundog. He was bright; there’d been a place for him in his colony’s soviet. But he had been driven to ask uncomfortable questions, to think uncomfortable thoughts.

Once, a sense of moral righteousness had lent him strength. That youthful smugness was long gone now, but he still had pity and the willingness to help. For Ryumin, decency had become an old man’s habit.

The young sundog twisted in his sleep. His face seemed to ripple, twisting bizarrely. Ryumin squinted in surprise. This man was a strange one. That was nothing remarkable; the System was full of the strange. It was when they escaped control that things became interesting.

Lindsay woke, groaning. “How long have I been out?” he said.

“Three hours, twelve minutes,” Ryumin said. “But there’s no day or night here, Mr. Dze. Time doesn’t matter.”

Lindsay propped himself up on one elbow.

“Hungry?” Ryumin passed Lindsay a bowl of soup.

Lindsay looked uneasily at the warm broth. Circles of oil dotted its surface and white lumps floated within it. He had a spoonful. It was better than it looked.

“Thank you,” he said. He ate quickly. “Sorry to be troublesome.”

“No matter,” Ryumin said. “Nausea is common when Zaibatsu microbes hit the stomach of a newcomer.”

“Why’d you follow me with that camera?” Lindsay said.

Ryumin poured himself a bowl of soup. “Curiosity,” he said. “I have the Zaibatsu’s entrance monitored by radar. Most sundogs travel in factions. Single passengers are rare. I wanted to learn your story. That’s how I earn my living, after all.” He drank his soup. “Tell me about your future, Mr. Dze. What are you planning?”

“If I tell you, will you help me?”

“I might. Things have been dull here lately.”

“There’s money in it.”

“Better and better,” Ryumin said. “Could you be more specific?”

Lindsay stood up. “We’ll do some acting,” he said, straightening his cuffs. “‘To catch birds with a mirror is the ideal snare,’ as my Shaper teachers used to say. I knew of the Black Medicals in the Ring Council. They’re not genetically altered. The Shapers despised them, so they isolated themselves. That’s their habit, even here. But they hunger for admiration, so I made myself into a mirror and showed them their own desires. I promised them prestige and influence, as patrons of the theatre.” He reached for his jacket. “But what does the Geisha Bank want?”

“Money. Power,” Ryumin said. “And the ruin of their rivals, who happen to be the Black Medicals.”

“Three lines of attack.” Lindsay smiled. “This is what they trained me for.” His smile wavered, and he put his hand to his midriff. “That soup,” he said. “Synthetic protein, wasn’t it? I don’t think it’s going to agree with me.”

Ryumin nodded in resignation. “It’s your new microbes. You’d better clear your appointment boo

k for a few days, Mr. Dze. You have dysentery.”

Chapter 2

THE MARE TRANQUILLITATIS PEOPLE’S CIRCUMLUNAR ZAIBATSU: 28-12-’15

Night never fell in the Zaibatsu. It gave Lindsay’s sufferings a timeless air: a feverish idyll of nausea.

Antibiotics would have cured him, but sooner or later his body would have to come to terms with its new flora. To pass the time between spasms, Ryumin entertained him with local anecdotes and gossip. It was a complex and depressing history, littered with betrayals, small-scale rivalries, and pointless power games.

The algae farmers were the Zaibatsu’s most numerous faction, glum fanatics, clannish and ignorant, who were rumored to practice cannibalism. Next came the mathematicians, a proto-Shaper breakaway group that spent most of its time wrapped in speculation about the nature of infinite sets. The Zaibatsu’s smallest domes were held by a profusion of pirates and privateers: the Hermes Breakaways, the Gray Torus Radicals, the Grand Megalics, the Soyuz Eclectics, and others, who changed names and personnel as easily as they cut a throat. They feuded constantly, but none dared challenge the Nephrine Black Medicals or the Geisha Bank. Attempts had been made in the past. There were appalling legends about them.

The people beyond the Wall had their own wildly varying mythos. They were said to live in a jungle of overgrown pines and mimosas. They were hideously inbred and afflicted with double thumbs and congenital deafness.

Others claimed there was nothing remotely human beyond the Wall: just a proliferating cluster of software, which had acquired a sinister autonomy.

It was, of course, possible that the land beyond the Wall had been secretly invaded and conquered by—aliens. An entire postindustrial folklore had sprung up around this enthralling concept, buttressed with ingenious arguments. Everyone expected aliens sooner or later. It was the modern version of the Millennium.

Ryumin was patient with him; while Lindsay slept feverishly, he patrolled the Zaibatsu with his camera robot, looking for news. Lindsay turned the corner on his illness. He kept down some soup and a few fried bricks of spiced protein.

One of Ryumin’s stacks of equipment began to chime with a piercingly clear electronic bleeping. Ryumin looked up from where he sat sorting cassettes. “That’s the radar,” he said. “Hand me that headset, will you?”

Lindsay crawled to the radar stack and untangled a set of Ryumin’s adhesive eyephones. Ryumin clamped them to his temples. “Not much resolution on radar,” he said, closing his eyes. “A crowd has just arrived. Pirates, most likely. They’re milling about on the landing pad.”

He squinted, though his eyes were already shut. “Something very large is moving about with them. They’ve brought something huge. I’d better switch to telephoto.” He yanked the headset’s cord and its plug snapped free.

“I’m going outside for a look,” Lindsay said. “I’m well enough.”

“Wire yourself up first,” Ryumin said. “Take that earset and one of the cameras.”

Lindsay attached the auxiliary system and stepped outside the zippered airlock into the curdled air.

He backed away from Ryumin’s dome toward the rim of the land panel. He turned and trotted to a nearby stile, which led over the low metal wall, and trained his camera upward.

“That’s good,” came Ryumin’s voice in his ear. “Cut in the brightness amps, will you? That little button on the right. Yes, that’s better. What do you make of it, Mr. Dze?”

Lindsay squinted through the lens. Far above, at the northern end of the Zaibatsu’s axis, a dozen sundogs were wrestling in free-fall with a huge silver bag.

“It looks like a tent,” Lindsay said. “They’re inflating it.” The silver bag wrinkled and tumesced suddenly, revealing itself as a blunt cylinder. On its side was a large red stencil as wide as a man was tall. It was a red skull with two crossed lightning bolts.

“Pirates!” Lindsay said.

Ryumin chuckled. “I thought as much.”

A sharp gust of wind struck Lindsay. He lost his balance on the stile and looked behind him suddenly. The glass window strip formed a long white alley of decay. The hexagonal metaglass frets were speckled with dark plugs, jackstrawed here and there with heavy reinforcement struts. Leaks had been sprayed with airtight coats of thick plastic. Sunlight oozed sullenly through the gaps.

“Are you all right?” Ryumin said.

“Sorry,” Lindsay said. He tilted the camera upward again.

The pirates had gotten their foil balloon airborne and had turned on its pair of small pusher-propellers. As it drifted away from the landing pad, it jerked once, then surged forward. It was towing something—an oddly shaped dark lump larger than a man.

“It’s a meteorite,” Ryumin told him. “A gift for the people beyond the Wall. Did you see the dark rocks that stand in the Sterilized Zone? They’re all gifts from pirates. It’s become a tradition.”

“Wouldn’t it be easier to carry it along the ground?”

“Are you joking? It’s death to set foot in the Sterilized Zone.”

“I see. So they’re forced to drop it from the air. Do you recognize these pirates?”

“No,” Ryumin said. “They’re new here. That’s why they need the rock.”

“Someone seems to know them,” Lindsay said. “Look at that.”

He focused the camera to look past the airborne pirates to the sloping gray-brown surface of the Zaibatsu’s third land panel. Most of this third panel was a bleak expanse of fuzz-choked mud, with surging coils of yellowish ground fog.

Near the third panel’s blasted northern suburbs was a squat, varicolored dome, built of jigsawed chunks of salvaged ceramic and plastic. A foreshortened, antlike crowd of sundogs had emerged from the dome’s airlock. They stared upward, their faces hidden by filter masks. They had dragged out a large crude machine of metal and plastic, fitted with pinions, levers, and cables. They jacked the machine upward until one end of it pointed into the sky.

“What are they doing?” Lindsay said.

“Who knows?” Ryumin said. “That’s the Eighth Orbital Army, or so they call themselves. They’ve been hermits up till now.”

The airship passed overhead, casting blurred shadows onto all three land panels. One of the sundogs triggered the machine.

A long metal harpoon flicked upward and struck home. Lindsay saw metal foil rupture in the airship’s tail section. The javelin gleamed crazily as it whirled end over end, its flight disrupted by the collision and the curve of Coriolis force. The metal bolt vanished into the filthy trees of a ruined orchard.

The airship was in trouble. Its crew kicked and thrashed in midair, struggling to force their collapsing balloon away from the ground attackers.

The massive stone they were towing continued its course with weightless, serene inertia. As its towline grew tight, it slowly tore off the airship’s tail.

With a whoosh of gas, the airship crumpled into a twisted metal rag. The engines fell, tugging the metal foil behind them in a rippling streamer.

The pirates thrashed as if drowning, struggling to stay within the zone of weightlessness. Their plight was desperate, since the zone was riddled with slow, sucking downdrafts that could send fliers tumbling to their deaths.

The rock blundered into the rippling edge of a swollen cloudbank. The dark mass veered majestically downward, wobbling a bit, and vanished into the mist. Moments later it reappeared below the cloud, plummeting downward in a vicious Coriolis arc.

It slammed into the glass and patchwork of the window strip. Lindsay, following it with his camera, heard the sullen crunch of impact. Glass and metal grated and burst free in a sucking roar.

The belly of the cloud overhead bulged downward and began to twist. A white plume spread above the blowout with the grace of creeping frost. It was steam, condensing from the air in the suddenly lowered pressure.

Lindsay held the camera above his head and leaped down onto the grimy floor of the window. He ran toward the blowout, ignoring Ryumin’s sur

prised protests.

A minute’s broken-field running brought him as close as he dared go. He crouched behind the rusted steel strut of a plug, ten meters from the impact site. Looking down past his feet through the dirty glass, Lindsay saw a long tail of freezing spray fanning out in rainbowed crystals against the shine of the sunlight mirrors.

A roaring vortex of sucking wind sprang up, slinging gusts of rain. Lindsay cupped one hand around the camera’s lens.

Motion caught his eye. A group of oxygen farmers in masks and coveralls were struggling across the glass from the bordering panel. They cradled a long hose in their arms. They lurched forward doggedly, staggering in the wind, weaving among the plugs and struts.

Caught by the wind, a camouflaged surveillance plane crashed violently beside the hole. Its wreckage was sucked through at once.

The hose jerked and bucked with a gush of fluid. A thick spray of gray-green plastic geysered from its nozzle, hardening in midair. It hit the glass and clung there.

Under the whirlwind’s pressure the plastic warped and bulged, but held. As more gushed forth, the wind was choked and became a shrill whistle.

Even after the blowout was sealed, the farmers continued to pump plastic sludge across the impact zone. Rain fell steadily from the agitated clouds. Another knot of farmers stood along the window wall, leaning their masked heads together and pointing into the sky.

Lindsay turned and looked upward with the rest.

The sudden vortex had spawned a concentric surf of clouds. Through a crescent-shaped gap, Lindsay saw the dome of the Eighth Orbital Army, across the width of the Zaibatsu. Tiny forms in white suits ringed the dome, lying on the ground. They did not move.

Lindsay focused the telephoto across the interior sky. The fanatics of the Eighth Orbital Army lay sprawled on the fouled earth. A knot of them had been caught trying to escape into the airlock; they lay in a tangle, their arms outstretched.

He saw no sign of the airship pirates. He thought for a moment that they had all escaped back to the landing port. Then he spotted one of them, mashed flat against another window panel.

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

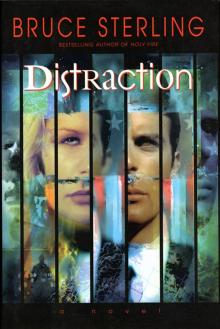

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase