- Home

- Bruce Sterling

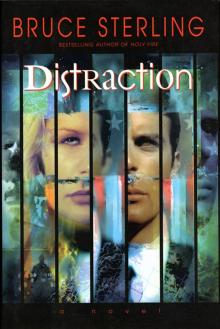

Distraction Page 3

Distraction Read online

Page 3

Oscar listened attentively.

“Y’know, the commander here was given no choice. No choice at all. It was pull this stunt, or watch his people starving in their barracks. There’s no funding now. There’s no fuel, no pay for the troops, no equipment, there is nothing. All because you silk-suit sons of bitches in Washington can’t get it together to pass a budget.”

“My man just got to Washington,” Oscar said. “We need a chance.”

“My man here is a decorated officer! He was in Panama Three, Iraq Two, he was in Rwanda! He’s no politician—he’s a goddamn national hero! Now the feds are cracking up, and the Governor’s gone crazy, but the commander, he’ll be the fall guy for this. When it’s all over, he’ll be the man who has to pay for everything. The committees will break him in half.”

Oscar was calm. “That’s why I have to work in Washington.”

“What’s your party?”

“Senator Bambakias was elected with a thirty-eight percent plurality,” Oscar said. “He isn’t tied to any single party doctrine. He has multipartisan appeal.”

The PR man snorted. “What’s your party, I said.”

“Federal Democrat.”

“Aw Jesus.” The man ducked his head and waved one hand. “Go home, Yankee. Go get a life.”

“We were just leaving,” Fontenot said, putting aside his untouched bourbon. “You happen to know a good local restaurant? A Cajun place, I mean? It has to seat a dozen of us.”

__________

The young guard at the door saluted politely as they left the hospitality building. Oscar carefully slipped his federal ID back into his eelskin wallet. He waited until they were well out of earshot before he spoke. “He may be dead drunk, but that guy sure knows the local restaurants.”

“Journalists always remember these things,” Fontenot said wisely. “Y’know something? I know that guy. I met him once, at Battledore’s in Georgetown. He was doing lunch with the Vice President at the time. I can’t remember his name now for the life of me, but that’s his face all right. He was a big-name foreign correspondent once, a big wheel on the old TV cable nets. That was before they outed him as a U.S. infowar spook.”

Oscar considered this. As a political consultant, he had naturally come to know many journalists. He had also met a certain number of spooks. Journalists certainly had their uses in the power game, but spooks had always struck him as a malformed and not very bright subspecies of political consultant. “Did you happen to tape that little discussion we just had?”

“Yeah,” Fontenot admitted. “I generally do that. Especially when I’m dead sure that the other guy is also taping it.”

“Good man,” Oscar said. “I’ll be skimming the highlights of that conversation and passing them on to the Senator.”

Oscar and Fontenot’s relations during the campaign had always been formal and respectful. Fontenot was twice Oscar’s age, canny, and paranoid, always entirely and utterly serious about assuring the physical safety of the candidate. With the campaign safely behind them, though, Fontenot had clearly been loosening. Now he seemed inspired by a sudden attack of sincerity. “Would you like a little advice? You don’t have to listen, if you don’t want to.”

“You know I always listen to your advice, Jules.”

Fontenot looked at him. “You want to be Bambakias’s chief of staff in Washington.”

Oscar shrugged. “Well, I never denied that. Did I ever deny it?”

“Stick with your Senate committee job, instead. You’re a clever guy, and I think maybe you could accomplish something in Washington. I’ve seen you run those hopeless goofballs in your krewe like they were a crack army, so I just know you could handle a Senate committee. And something’s just gotta get done.” Fontenot looked at Oscar with genuine pain. “America has lost it. We can’t get a grip. Goddammit, just look at all this! Our country’s up on blocks.”

“I want to help Bambakias. He has ideas.”

“Bambakias can give a good speech, but he’s never lived a day inside the Beltway. He doesn’t even know what that means. The guy’s an architect.”

“He’s a very clever architect.”

Fontenot grunted. “He wouldn’t be the first guy who mistook intelligence for political smarts.”

“Well, I suppose the Senator’s ultimate success depends on his handlers. The Senate krewe, the entourage. His staff.” Oscar smiled. “Look, I didn’t hire you, you know. Bambakias hired you. The man can make good staff decisions. All he needs is a chance.”

Fontenot flipped up his yellow coat collar. It had begun to drizzle.

Oscar spread his manicured hands. “I’m only twenty-eight years old. I don’t have the necessary track record to become a Senator’s chief of staff. And besides, I’m about to have my hands full with this Texas science assignment.”

“And besides,” Fontenot mimicked, “there’s your little personal background problem.”

Oscar blinked. It always gave him an ugly moment of vertigo to hear that matter mentioned aloud. Naturally Fontenot knew all about the “personal background problem.” Fontenot made knowing such things his business. “You don’t hold that problem against me, I hope.”

“No.” Fontenot lowered his voice. “I might have. I’m an old man, I’m old-fashioned. But I’ve seen you at work, so I know you better now.” He thumped his artificial leg against the ground. “That’s not why I’m leaving you, Oscar. But I am leaving. The campaign’s over, you won. You won big. I’ve done a lot of campaigns in my day, and I really think yours may have been the prettiest I ever saw. But now I’m back home to the bayous, and it’s time for me to leave the business. Forever. I’m gonna see your convoy safely through to Buna, then I’m outta here.”

“I respect that decision, I truly do,” Oscar said. “But I’d prefer it if you stayed on with us—temporarily. The crew respects your professional judgment. And the Buna situation might need your security skills.” Oscar drew a breath, then started talking with more focus and intensity. “I haven’t exactly broken this to our boys and girls on the bus, but I’ve been scoping out the Buna situation. And this delightful Texas vacation retreat that’s our destination tonight—basically, it looks to me like a major crisis waiting to happen.”

Fontenot shook his head. “I’m not in the market for a major crisis. I’ve been looking forward to retirement. I’m gonna fish, I’m gonna hunt a little. I’m gonna get myself a shack in the bayou that has a stove and a fryin’ pan, and no goddamn nets or telephones, ever, ever again.”

“I can make it worth your while,” Oscar coaxed. “Just a month, all right? Four weeks till the Christmas holidays. You’re still on salary, as long as you’re with us. I can double that if I have to. Another month’s pay.”

Fontenot wiped rain from his hat brim. “You can do that?”

“Well, not directly, not from the campaign funds, but Pelicanos can handle it for us. He’s a wizard at that sort of thing. Two months’ salary for one month’s work. And at Boston rates, too. That might swing the earnest money on your standard bayou shack.”

Fontenot was weakening. “Well, you’ll have to let me think that over.”

“You can have weekends.”

“Really?”

“Three-day weekends. Since you’re looking for a place to live.”

Fontenot sighed. “Well…”

“Audrey and Bob wouldn’t mind doing some real-estate scanning for you. They’re world-class oppo research people, and they’re just killing time out here. So why should you get taken in a house deal? They can scare you up a dream home, and even a decent real-estate agent.”

“Damn. I never thought of that angle. That’s true, though. That could be worth a lot to me. It’d save me a lot of trouble. All right, I’ll do it.”

They shook hands.

They had reached their vehicles. There was no sign of Norman-the-Intern, however. Fontenot stood up on the dented hood of his hummer, his prosthetic leg squeaking with the effort, and finally sp

otted Norman with his binoculars.

Norman was talking with some Air Force personnel. They were clustered together under the sloping roof of a concrete picnic table, next to a wooden walkway that led into the cypress-haunted depths of the Sabine River swamp. “Should I fetch him for you?” Fontenot said.

“I’ll get him,” Oscar said. “I brought him. You can call Pelicanos back at the bus, and brief the krewe on the situation.”

Young people were a distinct minority in contemporary America. Like most minorities, they tended to fraternize. Norman was young enough to be of military age. He was leaning against a graffiti-etched picnic roof support and haranguing the soldiers insistently.

“…radar-transparent flying drones with X-ray lasers!” Norman concluded decisively.

“Well, maybe we have those, and maybe we don’t,” drawled a young man in blue.

“Look, it’s common knowledge you have them. It’s like those satellites that read license plates from orbit—they’re yesterday’s news, you’ve had ’em for a zillion years. So my point is: given that technical capacity, why don’t you just take care of this Governor of Louisiana? Spot his motorcade with drone telephotos, and follow him around. When you see him wander out of the car a little ways, you just zap him.”

A young woman spoke up. “‘Zap’ Governor Huguelet?”

“I don’t mean kill him. That would be too obvious. I mean vaporize him. Just evaporate the guy! Shoes, suit, the works! They’d think he’s like…you know…off in some hotel chewing the feet of some hooker.”

It took the Air Force people some time to evaluate this proposal. The concept was clearly irritating them. “You can’t evaporate a whole human body with an airborne X-ray laser.”

“You could if it was tunable.”

“Tunable free-electron lasers aren’t radar-transparent. Besides, their power demand is out the roof.”

“Well, you could collate four or five separate aircraft into one overlapping fire zone. Besides, who needs clunky old free electrons when there are quantum-pitting bandgaps? Bandgaps are plenty tunable.”

“Sorry to interrupt,” Oscar said. “Norman, we’re needed back at the bus now.”

The Air Force girl stared at Oscar, slowly taking him in, from perfect hat to shiny shoes. “Who’s the suit?”

“He’s…well, he’s with the U.S. Senate.” Norman smiled cheerily. “Really good friend of mine.”

Oscar put a gentle hand on Norman’s shoulder. “We need to move along, Norman. We’ve just made a group reservation at a great Cajun restaurant.”

Norman tagged along obediently. “Will they let me drink there?”

“Laissez les bon temps rouler,” Oscar said.

“Those were nice kids,” Norman announced. “I mean, roadblockers and all, but basically, they’re just really nice American kids.”

“They’re American military personnel who are engaging in highway robbery.”

“Yeah. That’s true. It’s bad. It’s really too bad. Y’know? They’re stuck in the military, so they just don’t think politically.”

__________

They crossed the Texas border in the clammy thick of the night. The krewe was glutted with hot baked shrimp and batter-fried alligator tail, topped with seemingly endless rounds of blendered hurricanes and flaming brandied coffees. The food at the Cajun casinos was epic in scope. They even boasted a convenient special rate for tour buses.

It had been a very good idea to stop and eat. Oscar could sense that the mood of his miniature public had shifted radically. The krewe had really enjoyed themselves. They’d been repeatedly informed that they were in the state of Louisiana, but now they could feel that fact in their richly clotted bloodstreams.

This wasn’t Boston anymore. This was no longer the sordid tag end of the Massachusetts campaign. They were living in an interregnum, and maybe, somehow, if you only believed, in the start of something better. Oscar could not feel bad about his life. It was not a normal life and it never had been, but it offered very interesting challenges. He was rising to the next challenge. How bad could life be? At least they were all well fed.

Except for hardworking Jimmy the driver, who was paid specifically not to drink himself senseless, Oscar was the last person awake inside the bus. Oscar was almost always the last to sleep, as well as the first to wake. Oscar rarely slept at all. Since the age of six, he had customarily slept for about three hours a night.

As a small child, he would simply lay silently in darkness during those long extra hours of consciousness, quietly plotting how to manage the mad vagaries of his adoptive Hollywood parents. Surviving the Valparaiso household’s maelstrom of money, drugs, and celebrity had required a lot of concentrated foresight.

In his later life, Oscar had put his night-owl hours to further good use: first, the Harvard MBA. Then the biotechnology start-up, where he’d picked up his long-time accountant and finance man, Yosh Pelicanos, and also his faithful scheduler/receptionist, Lana Ramachandran. He’d kept the two of them on through the cash-out of his first company, and on through the thriving days of venture capital on Route 128. Business strongly suited Oscar’s talents and proclivities, but he had nevertheless moved on swiftly, into political party activism. A successful and innovative Boston city council campaign had brought him to the attention of Alcott Bambakias. The U.S. Senate campaign then followed. Politics had become the new career. The challenge. The cause.

So Oscar was awake in darkness, and working. He generally ended each day with a diary annotation, a summary of the options taken and important operational events. Tonight, he wrapped up his careful annotations of the audiotape with the Air Force highway bandits. He shipped the file to Alcott Bambakias, encrypted and denoted “personal and confidential.” There was no way to know if this snippet of the modern chaos in Louisiana would capture his patron’s mercurial attention. But it was necessary to keep up a steady flow of news and counsel across the net. To be out of the Senator’s sight might be very useful in some ways, but to drift out of his mind would be a professional blunder.

Oscar composed and sent a friendly net-note to his girlfriend, Clare, who was living in his house in Boston. He studied and updated his personnel files. He examined and totaled the day’s expenditures. He composed his daily diary entries. He took comfort in the strength of his routines.

He had met many passing setbacks, but he had yet to meet a challenge that could conclusively defeat him.

He shut his laptop with a sense of satisfaction, and prepared himself for sleep. He twitched, he thrashed. Finally he sat up, and opened his laptop again.

He studied the Worcester riot video for the fifty-second time.

The scientist wore plaid bermuda shorts, a faded yellow tank top, flip-flop sandals, and no hat. Oscar was prepared to tolerate their guide’s bare and bony legs, and even his fusty beard. But it was hard to take a man entirely seriously when he lacked a proper hat.

The beast in question was dark green, very fibrous, and hairy. This was a binturong, a mammal once native to Southeast Asia, long since extinct in the wild. This specimen had been cloned on-site at the Buna National Collaboratory. They’d grown it inside the altered womb of a domestic cow.

The cloned binturong was hanging from the underside of a park bench, clinging to the wooden slats. It was licking at paint chips, with a narrow, spotted tongue. The binturong was about the size of a well-stuffed golf bag.

“Your specimen is remarkably tame,” said Pelicanos politely, holding his hat in his hand.

The scientist shook his bearded head. “Oh, we never claim that we ‘tame’ animals here at the Collaboratory. He’s been de-feralized. But he’s not what you’d call friendly.”

The binturong detached itself from the bench slats and trundled through the lush grass on its bearlike paws.

The beast examined Oscar’s leather shoes, lifted its pointed snout in disgust, and muttered like a maladjusted kettle. At such close and intimate range, the nature of the animal became mo

re apparent to Oscar. A binturong was akin to a weasel. A large, tree-climbing weasel. With a hairy, prehensile tail. Also, it stank.

“We seem to be in the market for a binturong,” Oscar said, smiling. “Do you wrap them up in brown paper?”

“If you mean how do we get this sample specimen to your friend the Senator…well, we can do that through channels.”

Oscar arched his brows. “‘Channels’?”

“Channels, you know…Senator Dougal had his people handling that sort of thing…” Their guide trailed off, suddenly guilty and jittery, as if he’d drunk the last of the office coffee and neglected to change the pot. “Look, I’m just a lab guy, I don’t really know much about that. You should ask the people at Spinoffs.”

Oscar unfolded his laminated pocket map of the Buna National Collaboratory. “And where would ‘Spinoffs’ be?”

The guide tapped helpfully at Oscar’s plastic map. His hands were stained with chemicals and his callused thumb was a nice dull green. “Spinoffs was the building just on your left as you drove in through the main airlock.”

Oscar squinted at the map’s fine print. “The Archer Parr Memorial Competitive Enhancement Facility?”

“Yeah, that’s the place. Spinoffs.”

Oscar gazed upward, adjusting the brim of his hat against the Texas sun. A huge nexus of interlocking struts cut the sky overhead, like the exoskeleton of a monster diatom. The distant struts were great solid stony beams, holding greenhouse panes of plastic the size of hockey rinks. The federal lab had been funded, created, and built in an age when recombinant DNA had been considered as dangerous as nuclear power plants. The dome of the Buna National Collaboratory had been designed to survive tornadoes, hurricanes, earthquakes, a saturation bombing. “I’ve never been in a sealed environment so large it required its own map,” Oscar said.

“You get used to it.” Their guide shrugged. “You get used to the people who live in here, and even the cafeteria food…The Collaboratory gets to be home, if you stay in here long enough.” Their guide scratched at his furry jaw. “Except for East Texas, outside the airlocks there. A lot of people never get used to East Texas.”

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase