- Home

- Bruce Sterling

GURPS' LABOUR LOST Page 2

GURPS' LABOUR LOST Read online

Page 2

Lured by the scent of money, other game companies were champing at the bit. Blankenship reasoned that the time had come for a real “Cyberpunk” gaming-book — one that the princes of computer-mischief in the Legion of Doom could play without laughing themselves sick. This book, GURPS Cyberpunk, would reek of culturally on-line authenticity.

Hot discussion soon raged on the Steve Jackson Games electronic bulletin board, the “Illuminati BBS.” This board was named after a bestselling SJG card-game, involving antisocial sects and cults who war covertly for the domination of the world. Gamers and hackers alike loved this board, with its meticulously detailed discussions of pastimes like SJG’s “Car Wars,” in which souped-up armored hot-rods with rocket-launchers and heavy machine-guns do battle on the American highways of the future.

While working, with considerable creative success, for SJG, Blankenship himself was running his own computer bulletin board, “The Phoenix Project,” from his house. It had been ages — months, anyway — since Blankenship, an increasingly sedate husband and author, had last entered a public phone-booth without a supply of pocket-change. However, his intellectual interest in computer-security remained intense. He was pleased to notice the presence on “Phoenix” of Henry Kluepfel, a phone-company security professional for Bellcore. Such contacts were risky for telco employees; at least one such gentleman who reached out to the hacker underground had been accused of divided loyalties and summarily fired. Kluepfel, on the other hand, was bravely engaging in friendly banter with heavy-dude hackers and eager telephone-wannabes. Blankenship did nothing to spook him away, and Kluepfel, for his part, passed dark warnings about “Phoenix Project” to the Chicago group. “Phoenix Project” glowed with the radioactive presence of the E911 document, passed there in a copy of Craig Neidorf’s electronic hacker fan-magazine, Phrack.

“Illuminati” was prominently mentioned on the Phoenix Project. Phoenix users were urged to visit Illuminati, to discuss the upcoming “cyberpunk” game and possibly lend their expertise. It was also frankly hoped that they would spend some money on SJG games.

Illuminati and Phoenix had become two ripe pumpkins on the criminal vine.

Hacker busts were nothing new. They had always been somewhat problematic for the authorities. The offenders were generally high-IQ white juveniles with no criminal record. Public sympathy for the phone companies was limited at best. Trials often ended in puzzled dismissals or a slap on the wrist. But the harassment suffered by “the business community” — always the best friend of law enforcement — was real, and highly annoying both financially and in its sheer irritation to the target corporation.

Through long experience, law enforcement had come up with an unorthodox but workable tactic. This was to avoid any trial at all, or even an arrest. Instead, somber teams of grim police would swoop upon the teenage suspect’s home and box up his computer as “evidence.” If he was a good boy, and promised contritely to stay out of trouble forthwith, the highly expensive equipment might be returned to him in short order. If he was a hard-case, though, too bad. His toys could stay boxed-up and locked away for a couple of years.

The busts in Austin were an intensification of this tried-and-true technique. There were adults involved in this case, though, reeking of a hardened bad-attitude. The supposed threat to the 911 system, apparently posed by the E911 document, had nerved law enforcement to extraordinary effort. The 911 system is, of course, the emergency dialling system used by the police themselves. Any threat to it was a direct and insolent hacker menace to the electronic home-turf of American law enforcement.

Had Steve Jackson been arrested and directly accused of a plot to destroy the 911 system, the resultant embarrassment would likely have been sharp, but brief. The Chicago group, instead, chose total operational security. They may have suspected that their search for E911, once publicized, would cause that “dangerous” document to spread like wildfire throughout the underground. Instead, they allowed the misapprehension to spread that they had raided Steve Jackson to stop the publication of a book: GURPS Cyberpunk. This was a grave public-relations blunder which caused the darkest fears and suspicions to spread — not in the hacker underground, but among the general public.

On March 1, 1990, 21-year-old hacker Chris Goggans (aka “Erik Bloodaxe”) was wakened by a police revolver levelled at his head. He watched, jittery, as Secret Service agents appropriated his 300 baud terminal and, rifling his files, discovered his treasured source-code for the notorious Internet Worm. Goggans, a co-sysop of “Phoenix Project” and a wily operator, had suspected that something of the like might be coming. All his best equipment had been hidden away elsewhere. They took his phone, though, and considered hauling away his hefty arcade-style Pac-Man game, before deciding that it was simply too heavy. Goggans was not arrested. To date, he has never been charged with a crime. The police still have what they took, though.

Blankenship was less wary. He had shut down “Phoenix” as rumors reached him of a crackdown coming. Still, a dawn raid rousted him and his wife from bed in their underwear, and six Secret Service agents, accompanied by a bemused Austin cop and a corporate security agent from Bellcore, made a rich haul. Off went the works, into the agents’ white Chevrolet minivan: an IBM PC-AT clone with 4 meg of RAM and a 120-meg hard disk; a Hewlett-Packard LaserJet II printer; a completely legitimate and highly expensive SCO-Xenix 286 operating system; Pagemaker disks and documentation; the Microsoft Word word-processing program; Mrs. Blankenship’s incomplete academic thesis stored on disk; and the couple’s telephone. All this property remains in police custody today.

The agents then bundled Blankenship into a car and it was off the Steve Jackson Games in the bleak light of dawn. The fact that this was a business headquarters, and not a private residence, did not deter the agents. It was still early; no one was at work yet. The agents prepared to break down the door, until Blankenship offered his key.

The exact details of the next events are unclear. The agents would not let anyone else into the building. Their search warrant, when produced, was unsigned. Apparently they breakfasted from the local “Whataburger,” as the litter from hamburgers was later found inside. They also extensively sampled a bag of jellybeans kept by an SJG employee. Someone tore a “Dukakis for President” sticker from the wall.

SJG employees, diligently showing up for the day’s work, were met at the door. They watched in astonishment as agents wielding crowbars and screwdrivers emerged with captive machines. The agents wore blue nylon windbreakers with “SECRET SERVICE” stencilled across the back, with running-shoes and jeans. Confiscating computers can be heavy physical work.

No one at Steve Jackson Games was arrested. No one was accused of any crime. There were no charges filed. Everything appropriated was officially kept as “evidence” of crimes never specified. Steve Jackson will not face a conspiracy trial over the contents of his science-fiction gaming book. On the contrary, the raid’s organizers have been accused of grave misdeeds in a civil suit filed by EFF, and if there is any trial over GURPS Cyberpunk it seems likely to be theirs.

The day after the raid, Steve Jackson visited the local Secret Service headquarters with a lawyer in tow. There was trouble over GURPS Cyberpunk, which had been discovered on the hard-disk of a seized machine. GURPS Cyberpunk, alleged a Secret Service agent to astonished businessman Steve Jackson, was “a manual for computer crime.”

“It’s science fiction,” Jackson said.

“No, this is real.” This statement was repeated several times, by several agents. This is not a fantasy, no, this is real. Jackson’s ominously accurate game had passed from pure, obscure, small-scale fantasy into the impure, highly publicized, large-scale fantasy of the hacker crackdown. No mention was made of the real reason for the search, the E911 document. Indeed, this fact was not discovered until the Jackson search-warrant was unsealed by his EFF lawyers, months later. Jackson was left to believe that his board had been seized because he intended to publish a science fict

ion book that law enforcement considered too dangerous to see print. This misconception was repeated again and again, for months, to an ever-widening audience. The effect of this statement on the science fiction community was, to say the least, striking.

GURPS Cyberpunk, now published and available from Steve Jackson Games (Box 18957, Austin, Texas 78760), does discuss some of the commonplaces of computer-hacking, such as searching through trash for useful clues, or snitching passwords by boldly lying to gullible users. Reading it won’t make you a hacker, any more than reading Spycatcher will make you an agent of MI5. Still, this bold insistence by the Secret Service on its authenticity has made GURPS Cyberpunk the Satanic Verses of simulation gaming, and has made Steve Jackson the first martyr-to-the-cause for the computer world’s civil libertarians.

From the beginning, Steve Jackson declared that he had committed no crime, and had nothing to hide. Few believed him, for it seemed incredible that such a tremendous effort by the government would be spent on someone entirely innocent.

Surely there were a few stolen long-distance codes in “Illuminati,” a swiped credit-card number or two — something. Those who rallied to the defense of Jackson were publicly warned that they would be caught with egg on their face when the real truth came out, “later.” But “later” came and went. The fact is that Jackson was innocent of any crime. There was no case against him; his activities were entirely legal. He had simply been consorting with the wrong sort of people.

In fact he was the wrong sort of people. His attitude stank. He showed no contrition; he scoffed at authority; he gave aid and comfort to the enemy; he was trouble. Steve Jackson comes from subcultures — gaming, science fiction — that have always smelled to high heaven of troubling weirdness and deep-dyed unorthodoxy. He was important enough to attract repression, but not important enough, apparently, to deserve a straight answer from those who had raided his property and destroyed his livelihood.

The American law-enforcement community lacks the manpower and resources to prosecute hackers successfully, one by one, on the merits of the cases against them. The cyber-police to date have settled instead for a cheap “hack” of the legal system: a quasi-legal tactic of seizure and “deterrence.” Humiliate and harass a few ringleaders, the philosophy goes, and the rest will fall into line. After all, most hackers are just kids. The few grown-ups among them are sociopathic geeks, not real players in the political and legal game. And in the final analysis, a small company like Jackson’s lacks the resources to make any real trouble for the Secret Service.

But Jackson, with his conspiracy-soaked bulletin board and his seedy SF-fan computer-freak employees, is not “just a kid.” He is a publisher, and he was battered by the police in the full light of national publicity, under the shocked gaze of journalists, gaming fans, libertarian activists and millionaire computer entrepreneurs, many of whom were not “deterred,” but genuinely aghast.

“What,” reasons the author, “is to prevent the Secret Service from carting off my word-processor as ‘evidence’ of some non-existent crime?”

“What would I do,” thinks the small-press owner, “if someone took my laser-printer?”

Even the computer magnate in his private jet remembers his heroic days in Silicon Valley when he was soldering semi-legal circuit boards in a small garage.

Hence the establishment of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. The sherriff had shown up in Tombstone to clean up that outlaw town, but the response of the citizens was swift and well-financed.

Steve Jackson was provided with a high-powered lawyer specializing in Constitutional freedom-of-the-press issues. Faced with this, a markedly un-contrite Secret Service returned Jackson’s machinery, after months of delay — some of it broken, with valuable data lost. Jackson sustained many thousands of dollars in business losses, from failure to meet deadlines and loss of computer-assisted production.

Half the employees of Steve Jackson Games were sorrowfully laid-off. Some had been with the company for years — not statistics, these people, not “hackers” of any stripe, but bystanders, citizens, deprived of their livelihoods by the zealousness of the March 1 seizure. Some have since been re-hired — perhaps all will be, if Jackson can pull his company out of its persistent financial hole. Devastated by the raid, the company would surely have collapsed in short order — but SJG’s distributors, touched by the company’s plight and feeling some natural subcultural solidarity, advanced him money to scrape along.

In retrospect, it is hard to see much good for anyone at all in the activities of March 1. Perhaps the Jackson case has served as a warning light for trouble in our legal system; but that’s not much recompense for Jackson himself. His own unsought fame may be helpful, but it doesn’t do much for his unemployed co-workers. In the meantime, “hackers” have been vilified and demonized as a national threat. “Cyberpunk,” a literary term, has become a synonym for computer criminal. The cyber-police have leapt where angels fear to tread. And the phone companies have badly overstated their case and deeply embarrassed their protectors.

But sixteen months later, Steve Jackson suspects he may yet pull through. Illuminati is still on-line. GURPS Cyberpunk, while it failed to match Satanic Verses, sold fairly briskly. And SJG headquarters, the site of the raid, will soon be the site of Cyberspace Weenie Roast to start an Austin chapter of the Electronic Frontier Foundation. Bring your own beer.

FB2 document info

Document ID: bd8ea373-6c2b-1014-aab8-dd67f207bc1c

Document version: 1

Document creation date: 31.05.2008

Created using: Text2FB2 software

Document authors :

traum

About

This file was generated by Lord KiRon’s FB2EPUB converter version 1.1.5.0.

(This book might contain copyrighted material, author of the converter bears no responsibility for it’s usage)

�������� �������� ������������ ������ ������������ �������������������� FB2EPUB ������������ 1.1.5.0 ���������������������� Lord KiRon.

(������ ���������� ���������� ������������������ ���������������� �������������� �������������� ������������������ ������������, ���������� �������������������� ���� ���������� ������������������������������ ���� ������ ��������������������������)

http://www.fb2epub.net

https://code.google.com/p/fb2epub/

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

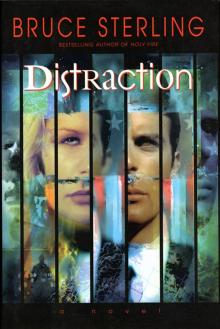

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase