- Home

- Bruce Sterling

Globalhead Page 12

Globalhead Read online

Page 12

She shook her head. “It’s the end, yes?”

“Could be,” he said. “But we’re still moving.” He scratched at his jaw. “Still alive. Still talking.” He gripped her hand. “You still feel that, right?”

“Yes.” She muttered something in Russian.

“What’s that mean?” he said.

“Let’s go in back,” she said. She tugged at his hand. “Let’s go in back, together. Come on, Jim, I’ll let you.”

He wondered why she thought that would help any. He didn’t bother to ask it. Sounded okay, actually. Nothing left to lose.

They got into the back, unrolled the sleeping bag, took some clothes off and fought their way inside it. It was cramped, uncomfortable, full of knees and elbows.

They did it. It was not much good. Clumsy, tense, unpleasant. Some time passed, with much harsh breathing. They tried it again from another position. It was somewhat improved, this time.

They were very tired then, and fell asleep.

Jim woke. There was sunlight in the van. He unzipped the bag down the side, crawled out, got into his jeans.

Irene woke up, hard and sluggishly, heavy-lidded and squinting. She groaned aloud, a harsh, complaining sound, and got up on one elbow.

She ran her hand through her hair, as if her scalp hurt. “Was I drunk?” she said.

“No,” he said. “Might’ve helped, though.” He found his boots. “Don’t you ever relax?”

“Don’t complain, Jim,” she said testily. “You relax first, then maybe I relax.” She sat up. “My head feels funny.” She found her shirt.

Jim stood up, half-crouched. “We’re on the side of the highway,” he said. “Parked.”

He opened the back of the van, stepped out on the road shoulder. Crisp desert air, a cactus-clumped horizon, a couple of weathered Budweiser cans underfoot.

He threw his arms back, breathed hugely, stretched cramps out of his shoulder blades. He felt pretty good, all things considered. “Can’t be far to El Paso,” he said. He sniffed. “Hey! My cold is gone.” He thumped his chest. “Wow. That’s great.”

Irene crawled forward, squinting, set her feet on the bumper. She looked up. “What is that, in the sky?”

Jim glanced up. “Vapor trail. Jets, huh?”

She passed him his glasses. “Look again.”

Jim put his glasses on, looked up. The blue bowl of the desert sky looked scratched. It was full of spiderwebs. High distant threads, creeping things, capillaries, little ceramic cracks. “I’ll be damned,” he said. “Don’t that beat all.”

“Someone is coming,” Irene said.

It was an old pickup truck, a battered Ford. There was something attached to its roof. A thready twisting thing, like the base of a waterspout. As it went up it spewed itself out into yarn, a hundred directions, little vapor knots, knitted netting.

The truck passed them. A bespectacled farmer in a sweat-stained felt hat was driving it. The threads were attached to him, radiating out, a skein, an aura of them, not quite touching his skin.

As he neared them, he slowed down. He peered at them over the wheel, a little anxious for them. This was the desert, after all. Jim nodded, smiled broadly, shrugged. The farmer raised one weathered hand, nodded a bit, waved.

They watched him go. “Looks pretty good,” Jim commented. “Nice spry-looking old geezer. Kinda picturesque.”

“I’m hungry,” Irene said suddenly. “Want a big breakfast, Jim. Eggs, toast, flapcakes.”

“Good thinking, let’s roll.” They got into the front seats, fired up the van. Jim turned on the radio, skipped a news broadcast, found some cheery accordion music from over the border.

A tourist bus passed them. It was crowded, and the top of it was a roiling forest; blue, green, prismatic, flying up into the sky, a frayed and twisted veil, like flapping fiberglass laundry.

“You do see that stuff, right?” Jim said.

She nodded. “Yes, the threads, I see them, Jim.”

“Just checking.” He rubbed his unshaven chin. “Got any idea what it is?”

“It is the truth,” she said. “We can see the truth now. It’s how people live, Jim. The system of the world. All tied together.”

“Kinda weird looking.”

“Yes. But it has beauty.”

Jim nodded. It didn’t frighten him. It had been there, all around them, for a long time now. They just hadn’t been able to see it.

Irene passed her hand through the air above his head. “You have hardly any connections, Jim. Just a few threads, like thin hair.”

He checked her over. “You either. We’re not all wrapped up inside these thick nets of stuff, like most folks … Maybe that’s why we can see it so well. ’Cause we see it from the outside.”

Irene laughed. “It’s easy to see, when you know about it. I can feel it, Jim!”

He turned to her. “I feel it too.” Something was coming out from inside of him, hot and strong and radiant. A kind of fluid easy roiling, a glowing vapor from his skin, just coming clear. He batted at it with his free hand. It was like trying to catch a beam of light, or touch the sound of a laugh.

It moved toward Irene, merging with the tendril cloud that seethed around her. The air was full of her suddenly, wire-strong whipping threads the color of her stubborn eyes. For a moment it was a snarl of chaos, a scary murk of oil and water.

But then it was settling, with unsuspected grace, falling through itself, sifting into place. Love and fear and hate. Power, attraction … then the chaos was gone, turned to strong new threads as thin as old bad memories. Visible, only from a certain angle.

But they could still feel it. A bond between them. It was very strong.

THE SWORD

OF DAMOCLES

“The Sword of Damocles” is an ancient Greek story with the deeply satisfying structure of classical legend. It’s chock-full of eternal human truths, which, believe-you-me, still have plenty of meaning and relevance, even for our so-called-sophisticated, postmodern generation.

I’ve been looking the story over lately, and the material is great. It’s just a question of filing off a few serial numbers, and bringing it up-to-date. So here we go.

Once upon a time, there was a man named Damocles, a minor courtier at the palace of Dionysius, Tyrant of Syracuse. Damocles was unhappy with his role, and he envied the splendor of the Tyrant.

Actually the term “Tyrant” is a bit misleading here, because it didn’t mean at the time what it means today. All “tyrant” really meant was that Dionysius (405 B.C.—367 B.C.) had seized the government by force, rather than coming to power legitimately. It doesn’t necessarily mean that Dionysius was an evil thug. After all, it’s results that count, and sometimes one has to bend the rules a bit, just to get things started.

Take this “Once upon a time” business I just used, for instance. It starts the story all right, but it doesn’t sound very Greek, when you come right down to it. It’s more of a Grimm Brothers fairy-tale riff, kind of a kunstmarchen thing. Using it with a Greek myth is like putting a peaked Gothic spire on a Greek temple. Some people—Modernist critics—might say it’s a bad move aesthetically, and kind of bastardizes the whole artistic effort!

Of course, real hifalutin Modernist critics must have a pretty hard time of it lately. They must find life a trial. I bet they don’t watch much MTV. Modernists like coherent, systematic structures, but it’s all hybridized by now. Especially in the places that are really moving, like Tokyo. Postmodern Japan is like a giant Shinto temple with smokestacks. Culturally speaking, the whole place is a chimera, but people don’t criticize Japan’s set-up much, because capitalistically speaking they’re kicking everybody’s ass. Whatever works, man.

You know—this is amazing, but I swear it’s true—there are people nowadays who literally live in Tokyo “once upon a time.” They’re bankers and stockbrokers from New York and London, and they moved to Tokyo as expatriates, because they had to settle the Tokyo time-zone. It’s a fact

! Postmodern bankers have to do twenty-four-hour trading, and the stock market closes in New York hours before it opens in London. So nowadays all the big financial operators send people out to major markets all around the world, to colonize Time. “Time” is just another postmodern commodity now.

So that kind of blows my opening sentence, but the important thing is to get the story across. Simply, directly, in an unpretentious, naturalistic fashion. So forget the Gothic fairy-tale riff. I’m just gonna tell it straight. The way I’d talk to close friends, in my own living room, here in Austin, Texas.

So y’all listen up. There was this dude named Damocles, see, and he used to hang out in this palace, in Sicily. Ancient Sicily. Damocles was Greek though, not Italian, because, y’see, way back then … This was before Rome got started, and the Greeks were really good sailors, so they got all these remote colonies started up …

Okay, never mind the historical analysis, y’all. It’s kinda vital to the background, but I can’t get it across in this casual hick tone of voice without making it sound really goofy. So let’s stick to the drama, okay? The important plot-thing is that Damocles really envies his boss, this magnificent prince, Dionysius. So one day Damocles puts on his chiton—that’s a kind of Greek tunic—and his buskins—those were tall sandals like you see in the opera, if you ever go to those, which I don’t, personally. But you’ve probably seen them on public TV, right?

In fact, now that I mention it, since we’re all here in my living room, why don’t we just give this up, and watch some TV? I mean, forget this “oral storytelling tradition.” When was the last time you listened to some pal of yours tell a story out loud? I don’t mean lies about what he and his pals did last Friday, I mean a real myth-type story with a beginning, middle, and end. And a moral.

Let’s face it, we don’t really do that anymore. We postmoderns don’t live in an oral storytelling culture. If we want a story we can all enjoy together, we can rent a goddamn video. Near Dark is pretty good. My treat.

So, yeah—if I’m gonna make this work, it’s gonna have to be literary. It’ll have to hit some kind of high archaic note. We’ll have to really get into it—tell it, not like postmoderns, but just as the ancient Greeks would have told it. Simple, dignified, classical, and stately. Full of gravitas, and hubris, and similar impressive terms. We’ll cast a magic net of words, something to take us across the centuries … back to the authentic, ancestral world of Western culture!

So let’s envision it. We’re in an olive grove together, on a hillside in ancient Athens. I’m the mythagogue, probably some blind or lame guy, kept alive for my story-telling skills. I may be a slave, like Aesop. I’m making up (or reciting from memory) these marvelous mythic tales that will last forever, but I’m no particular big deal, personally.

You, my audience, on the other hand, look really great. You’re all young rambunctious aristocrats whose parents are paying for this. Your limbs are oiled, your hair is curled, and every one of you is a whiz at the discus and javelin. Some of you are naked, but nobody cares; even the snappiest dressers are essentially wearing table-cloths held together with big bronze pins.

Did I mention that you were all guys? Sorry, but yeah. Those of you who are young rambunctious women are, uhmmm … well, I’m afraid you’re off weaving chitons in the darkest part of your house. You don’t get to listen to mythagogues. It might give you ideas. In fact you don’t get to leave the house at all. We guys will be back to see you, sometime after midnight. After we get drunk with Socrates. Then we’ll have our jolly way with you.

And we’ll probably get you pregnant. Decent contraception hasn’t been invented yet. At least, not the nifty plastic-wrapped kinds people will use in the late twentieth century. That’s one reason why Damocles has a very dear male friend called Pythias.

But wait a sec—since I’m an authentic Greek mythagogue, I have to call him “Phyntias.” “Pythias” was called “Phyntias,” originally. A medieval scribe made a mistake transcribing the story in the fourteenth century, and he’s been “Pythias” ever since. There’s even a high-minded twentieth-century club called “The Pythian Society,” that’s named after a misprint! What a joke on them, huh? Goes to show what can happen if a storyteller gets careless!

So anyway, Damocles and Pythias were two close friends who lived in the court of Dionysius. One day, Damocles offended the Tyrant, and was sentenced to death. Damocles begged a few days’ mercy, to bid farewell to his family, who lived in another town.

But the cruel Dionysius refused him this mercy. At that point, the noble Pythias stepped forward. “I will stand in the place of my dear friend, Damocles,” he declared, to the assembled court. “If he does not return in seven days, I will die in his place!”

The vindictive heart of Dionysius was touched by this strange offer. Curious to see the outcome, he granted the boon. The two friends embraced and wept, and Damocles left to carry the sad news to his family. Pythias, in his place, was clapped in a dungeon. Days passed, one by one.

Wait a minute. Damn! Did I say “Damocles”? I meant “Damon.” It’s “Damon and Pythias,” not “Damocles.” Hell, I always get those two confused.

Christ on a Harley, man! I was off to such a great start, too. I was really rolling there for a minute. Now look at me! I don’t even have a character in my story. There’s no real character here except me, the author.

I can’t believe I got myself into this situation. I mean, that postmodernist lit-mag experimental stuff where authors use themselves as characters. That kind of crap really burns me up. I’m a sci-fi pop writer, myself. I write action-adventure stuff. Sure, it’s weird, but it’s not structurally weird; it’s weird ’cause it’s about weird ideas, like fractals and cranial jacks.

But now look at me. Not only am I a character in my own story, but my only real topic so far is “narrative structure.” I can’t stand it when postmodern critics talk about stories in terms like “narrative structure.” These hardhat deconstruction-workers harass stories as if they were gals passing by on the sidewalk. They yell out stuff that’s not only obnoxious, but completely bizarre and impenetrable. It’s like they yell: “Hey, check out the pelvic bio-mechanics on that babe! What a set of hypertrophied lactiferous tissues!”

I should have stuck to hard-SF, that’s my real problem. It was clear from the beginning this was going to be one of those weird-ass historical-fantasy things. I’m not even the proper author to be a character in this story. What this story needs is a character like Tim Powers, author of The Anubis Gates and On Stranger Tides.

“Suddenly, Tim Powers appeared. He looked about himself alertly.”

No, if I’m gonna do this at all, I’d better try it Powers-style.

“Suddenly, Tim Powers burst headlong into the story! His hair was on fire, and he was perched on a pair of stilts. Gnashing his teeth, he glared wildly from under layers of peeling clown-makeup and said:

“ ‘What the heck kind of fictional set-up is this? There’s nothing here but some kind of half-collapsed ancient Greek stage-set! I could do better research than this in my sleep! Anyway, I prefer Victoriana.’ ”

And then a voice emerged into the story from an area of narrative discourse that we can’t even reach from here. It said, “-‘-“Tim, what’s going on in there?”-’-”

And Powers said: “I dunno, sweetheart, I was just sitting here at the word-processor, and—ow! Somebody set my hair on fire! Serena, get the shotgun!”

Aw, jeez! … uhm:

“Tim Powers quickly disappeared from the story. The makeup disappeared from his face, and he looked just like he always did. And his hair stopped burning. There was no real damage done to it. He went into the bathroom of his Santa Ana apartment, got a comb, and lent fresh meaning to his hair. Then he forgot he had even been involved in this story.”

“ ‘Don’t bet on it, pal.’ ”

I swear it’ll never happen again. Don’t get mad! Lots of writers do it. Like the wife of Damocles, “Pandora.”

She’s not the original Greek-legend Pandora, wife of Epimetheus. Pandora hasn’t appeared in this story yet, but she’s a really interesting character. She likes to make blunt declarations to the reader, from a really weird narrative stance. Stuff like:

“ ‘Am I not the sister of Adolf Hitler and Anne Frank? Have I not eaten, drunk, and breathed poison all my life? Do you take me for an innocent, my colluding reader?’ ” That sort of thing.

“Pandora” is actually the thinly disguised author-character from Ursula K. Le Guin’s experimental SF epic Always Coming Home! How “Pandora” got into this story I’m not really sure, I guess it’s my mistake, but I’ll fight any man who claims that Always Coming Home isn’t “real SF”! Even if it’s not really, exactly, a “book.” For one thing, Always Coming Home has got an audiotape that comes with it, which puts a pretty severe dent in its narrative closure. I’d have liked to supply an audiotape with this story—maybe some Japanese pop music, or John Cage—but I was too cheap. Instead, I’ll just play the Always Coming Home tape here in my office. I ordered it from a P.O. box in Oregon. It’s got weird mellow chanting in made-up languages.

So much for Pandora. I was going to have a scene where Damocles wakes up in bed with Pandora, and she makes some biting remarks about having to weave the chitons and everything, but I guess you get the idea.

So here’s Damocles quickly leaving his home and going straight to work. He’s so eager to start the story that, not only does he jump right in with a Homeric “in medias res” routine, but he’s willing to settle for a breathless present-tense. Damocles works as a minor palace official in the court of Dionysius. Actually he’s a “flatterer,” according to Cicero’s Tusculan Disputations. He’s not a bureaucrat, like a postmodern official. There’s no bureaucracy in Syracuse, it’s all done by a tiny group of elite families, who run everything. Syracuse is a pre-industrial city-state of maybe fifty thousand people. An independent city-state about the size of Oshkosh, Wisconsin.

Damocles earns his living by making up flattering things about people who can kill him out-of-hand. He’s kind of a jackleg-poet crossed with a public-relations flack. He’s done pretty well by it, considering his lowly birth. He gets to eat meat almost every week. For most other Greeks of the period, common folk, there are two kinds of dietary staple. The first is a kind of mush, and the second is a kind of mush.

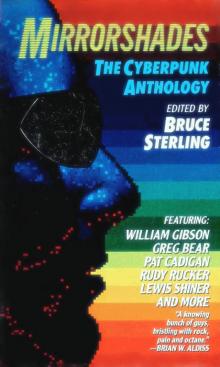

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology

Mirrorshades: The Cyberpunk Anthology The Wonderful Power of Storytelling

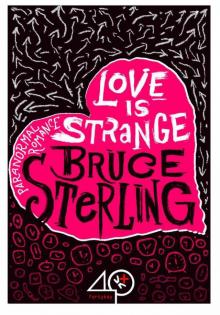

The Wonderful Power of Storytelling Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance)

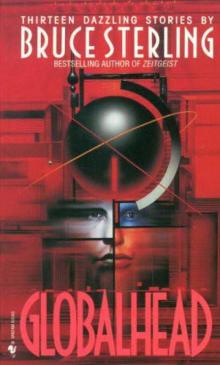

Love Is Strange (A Paranormal Romance) Globalhead

Globalhead Essays. FSF Columns

Essays. FSF Columns The Hacker Crackdown

The Hacker Crackdown Bicycle Repairman

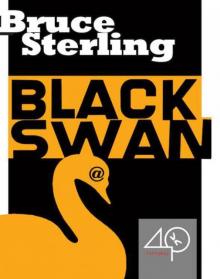

Bicycle Repairman Black Swan

Black Swan Crystal Express

Crystal Express Islands in the Net

Islands in the Net Pirate Utopia

Pirate Utopia GURPS' LABOUR LOST

GURPS' LABOUR LOST The Dead Media Notebook

The Dead Media Notebook Unstable Networks

Unstable Networks The Manifesto of January 3, 2000

The Manifesto of January 3, 2000 Heavy Weather

Heavy Weather Involution Ocean

Involution Ocean The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things

The Epic Struggle of the Internet of Things A Good Old-Fashioned Future

A Good Old-Fashioned Future The Littlest Jackal

The Littlest Jackal Zeitgeist

Zeitgeist Totem Poles

Totem Poles Ascendancies

Ascendancies CyberView 1991

CyberView 1991 War Is Virtual Hell

War Is Virtual Hell Taklamakan

Taklamakan Holy Fire

Holy Fire Cyberpunk in the Nineties

Cyberpunk in the Nineties Schismatrix Plus

Schismatrix Plus The Artificial Kid

The Artificial Kid Essays. Catscan Columns

Essays. Catscan Columns Maneki Neko

Maneki Neko Distraction

Distraction In Paradise

In Paradise Red Star, Winter Orbit

Red Star, Winter Orbit Luciferase

Luciferase